Rick and Morty - One Time Pad - Esoteric Languages

Memes as an internet subculture, World War era encryption schemes, and program states as stacks of dynamically sized integers, oh my! How do they all connect?

Problem Description

This content was brought to you by GRUMBOT

Went and found a wild esoteric language, spent a long time writing a masterful program in it, connected it all to the the smartest show on TV (don’t be a simpleton). Of course I one-time padded the source code. Then found the perfect episode of old R&M to tie it all together: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbcCsBj0b1U Well almost perfect, instead of a typical Western Morty vehicle we went another direction. (The esolang name does NOT contain the f-word.)

Here’s your ciphertext (the key is plain english, no spaces or punctuation, and 56 characters long)

Author: GRUMBOT and ProfNinja

Provided Ciphertext

3d1d0b0c1513001b0a06061b081f161d1c1b081f160805161b101b00141b20380706061d0d0c011a0712070d21001018080717241c011d10270611160f081a1b0a1c1c0112040c06061b21253628252c3b2a3b2034210002272626272d36213a2728273701203022283d37043c3b3d2a0726312c2f323a3b2a263c3b323f363d263b283f372824363b303b202e1820221d1c1c1d0d161b00100507173b1b0a02121c0d3e06011d0a3d1c0b160f120001101c1c1b08050c07061b08050c121f161b101b1b0e1a2d3807060607170c011a07081d0d21001002120717241c1b07102706110c15081a1b0a0b1c01121f1607060112040c131f0c010b0c0d0e1a2038071d1c07170c1b0006081c1721001002120717241c1b07102706110c15081a1b0a060601121f161d1c01121f1608050116101a000e1b3b381d06060717161b1a07081d173b001002121d0d241c1b070a3006100c0f121b16101d1c0112040c1d1c01080517080416010a0100141a2023100607070d1600171d13070d211b0a0212070d3e1d1b060a271c0b0c151300000a061c1b131f171d1c01121f1608050c01101b0d0e1b20221d1c1c1d0d161b001d1207173b1a070f050a0d3f061b070b3d1c0b160f120001101c1c1b08050c07061b08050c121f161b0a0100141a2023100607070d16001a1d12071721000a18081d172406011d0a27060b160f121a1b101c1c1b121f0c07061b121f0c121f160110011a0e1b3a381d1c0707160c011a07081d0d21001102081d16241d1b1d0a2606100c0f121b1b1006060112050c1d1c0112050108040c1b0a1a000e1b2038071d1c1c1716161a0608071720000a180807173f0600070a3d06110c151200001006061a081f161d061b131f1712050c1b0a1a0015012022060607070d16001a060507173b1a0a18050717241c1b07102706110c150500001006061a051f0c07061b08050c121f161b0a011a0e1b20221d1c1c1d0d161b001d12071721000a181307162406011d0a3d1c11010f13001b0a1d110108050c07061b08050c121f161b0a011a0e1b2022100607070d16001a1d12070d211b0a19121d0d3e1c161d0a3d1c0b160f120001101c1c1b05120c06060112040c121f161b0a011a0e1b20221d1c1c1d0d171b1a071307173b1a0a18081d0d3e061b070b3d1d0b0c151300001006061a0804011d061b08050c12050c0010011a150c203807060607170c011a070507163b0010190807172406010610261c11010f13001b0a1d1c01121f0c071d0113051608050c01101b1a03013a3807060607170c011a07081d0d210010021207172406010610260b060c140800010b061c1b08050c07061b08050c121f160110011a15013b380706060a000c001a1d121c0d3b1a0a18081d0d3e06011d0a3d1c0b160f120001101c1c1b08050c071c0c081f1608050c01101b0014013a221d06061c0d171b001d120a0d20000a18130a0d241c1b07102706110c15081a1b0a060601121f161d1c0c08040c0805171b101b000e1b3b38061c061d000c011a07081d0d21000a181307162906001d10271d060c0f120001101c1c1b08050c07061b08050c121f161b0a0c001501202206061c1d0d0c01011d131d173b1a100f081c0d241c0010102706110c15081a1b0a060601121f161d1c01121f160805011b0a011a0e1b2038071d1c1c0d0c011a07081d0d21001002121d0d241c001d0b30060b160f120001101c1c1b12120c07061b051f17081f16001d010014013a3807060607170c011a07081d0d21001002120717241c1b070a3d0611170f130001101c1101131f0c071d0c081f1608050c01101b0014013a38070606071716161a1d1207173b1a100f081c0d241c0010103d1c0b160f120001101c1c1b0805011d1d01080517081f161b101b1b0e1a3a221d1c06070d16001a06081d0d2100100212070d3e1d1b061d30060b160f1200010a0b1c01121f161d1c01121f16121f171b101b1b0e1a2038071d1c1c0d0c0101100807173b1a0a18081d0d3e0b1b06103d1c100c0f12001b0a1d1c1a1205011d1d01080517081f161b101b1b0e1a3a221d1c1c1d0d161b001d120717210d0a18081d0d241c001d0b3d0611170f13001b0a1d1c1a051f171d061b131f0c121f161b0a011a0e1b20221d1c1c1d000c001a1d121c0d3b1a0a02121c0d3f1c01071d3d06110c15120d1b0a06060c08050c07061b051f16051f0c01101b1a03013a3807061c1d160c00171d081d0d21001002120717241c1b071d3d1d0b0c1513001b0a061c1b131f17071c01120501081f161b0a1b0d0e013a3807060607170c011a070507163b0010190807172406010610261c11160f081a00

Rick and Morty XOR

The challenge description gives us a lot of information, so we immediately know this will be a multi-step challenge. The provided ciphertext is obviously hex encoded and the challenge mentions a one-time-pad so it appears we’ll be looking for a decryption key at first. We also know this decryption key is plain english words and exactly 56 characters long – so looks like it’s time to dive into the Rick and Morty video to see if we can find any clues.

A Background on OTPs and XOR

OTPs, or One-Time-Pads, are a form of encryption scheme in which every character in a plaintext is combined by some operation to a single character in a key to produce a single character in the ciphertext as shown in the form below.

plaintext: ABCDEFG

key: TUVWXYZ

ciphertext: MNOPQRS

First invented in the late 1800s but then accidentally reinvented in 1917 by the creation of the Vernam machine, OTPs have been consistently used since the first World War with some of their most notable uses taking place during the Cold War where messengers were given pages of numbers to use as keys that they were then told to destroy.

As a whole, a one-time-pad encryption scheme relies on 5 principles to be secure:

- The OTP (key) should consist of truely random characters

- The OTP should be at least the same length as the plaintext

- Only two copies of the OTP should exist.

- The OTP should be used only once.

- Both copies of the OTP are destroyed immediately after use.

The second principle stems from the fact that once all the characters of a key have been used to compare against the plaintext, the key begins to wrap around. This makes one-time-pads particularly vulnerable if the key is short and one can discern sequential patterns in the resultant ciphertext.

plaintext: A B C D E F G H

key: K E Y K E Y K E

ciphertext: S T U V W X Y Z

Just this principle alone usually isn’t enough to be able to break the key for a one-time-pad, but it reduces the complexity of bruteforcing by orders of magnitude in many cases. If, however, the key is in fact the same length as the plaintext then the one-time-pad qualifies to be a “stream cipher” – but more on that later.

Similarly, the fourth principle of key reuse makes one-time-pads vulnerable if multiple messages have been sent using the same key. If an eavesdropper could intercept multiple messages they could easily compare them to see similar patterns arising in the ciphertexts for words or sequences that occured in multiple messages.

Reusing the same key multiple times is referred to as increasing the “depth” of encryption where each additional layer of depth adds information about the plaintext into the ciphertext and can making the encrypted messages vulnerable to an attack known as “Crib Dragging” but I’ll save that for another article.

The most common operation used in modern applications of the one-time-pad scheme is the well-known XOR. If you’ve ever taken the time to look into logic gates or circuitry you may be familiar with it but what does that have to do with cryptography?

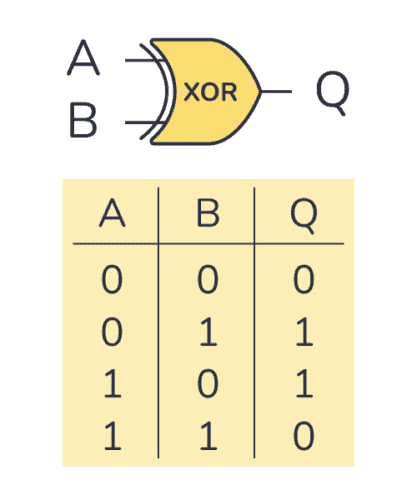

As seen by the image above, XOR works similarly to the OR logic expression but with the caveat that if the truth table for inputs A and B has both of them being 1 or “true” then XOR flips the resultant bit to a 0 or “false”. Now if you remember how I mentioned that XOR is a stream cipher we can begin to connect these bitwise operations to the properties of a stream cipher.

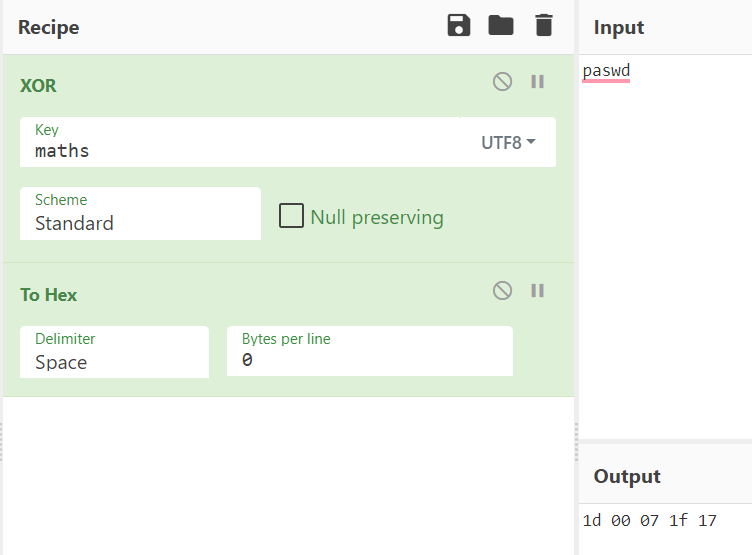

For a cipher to be a “stream cipher” it must apply a particular operation on every bit of a plaintext with its corresponding bit in the key. Say we want to encrypt the string “paswd” with a key of “maths”. We first convert each phrase to binary and then proceed to apply XOR for every bit of their binary representation to get our ciphertext.

plaintext: paswd

key: maths

plaintext binary: 01110000 01100001 01110011 01110111 01100100

key binary: 01101101 01100001 01110100 01101000 01110011

ciphertext binary: 00011101 00000000 00000111 00011111 00010111

ciphertext bytes: 1d 00 07 1f 17

Note: applying XOR on the second a character with itself in the key produced 00000000. As XOR of equivalent bits always produces 0 in the truth table, the XOR of any character or byte with itself will always be 0. While not relevant to the challenge at hand, if a 0/nullbyte is often present in the ciphertext it can reduce the complexity of bruteforcing or guessing the plaintext and key quite significantly showing why it is so important to have a random key.

This also reveals an additional special property of XOR in that it is reversible. For example:

A ⊕ B = C

∴ C ⊕ B = A and C ⊕ A = B

Many examples both in CTF challenges and real-world codebreaking are able to use property to find parts of the key if parts of the plaintext are known.

Going back to our XOR example and plugging our operation into our favorite encryption/decryption tool, CyberChef, we see that it holds as expected :)

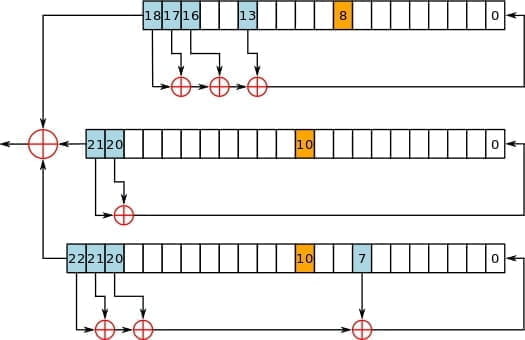

While XOR, if implemented correctly, is not the only stream one-time-pad operation, it is certainly the most common. The A5/1 standard for GSM (global standard for mobile communication), for example, is among the most popular encryption schemes for GSM phone calls and SMS messages in North America and Europe and is a stream cipher applying XOR as seen below:

Back to the Challenge At Hand

As is immediately obvious, our case of a hex string and unknown “rick and morty” related key violates properties 1 and 2 of a secure one-time-pad. While not explicitly stated I simply assumed for the challenge that the one-time-pad operation the challenge authors had used was XOR. Again, it is only one of many valid one-time-pad operations but considering it is the most common I felt that this was a valid assumption to make.

Watching the Rick and Morty episode linked in the challenge description and diving into the world of Rick and Morty meme internet subculture, I found this copypasta, which I found to be rather funny.

After enjoying my time staring at endless jokes about Pickle Rick and pre-teen “theoretical physics” commentary, coming very close to just bruteforcing the key, my teammate pointed out that the phrase “To be fair, you have to have a very high IQ to understand Rick and Morty” from the copypasta was exactly 56 characters long without spaces.

Eureka! This had to be it. Rather guessy and more OSINT than I was prepared for, but incredibly relieving to have the key. XORing the bytes we were given at the start of the challenge with the key “ToBeFairYouHaveToHaveaVeryHighIQtoUnderstandRickandMorty” we get a result of

irIiSriiSisSiisIsSiisiSsiiSissiisiSsiisissiisissiisissiisiSsIisiSsiIsriRiS@SSIsIISsISIISSIsIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSIsIiSSIsIIsSISiIsIIRIrSIIsIIpisisIsisisddisiriisrisisisisIsIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsiiSrirdisiSisisisisisisisisisisisiSiSisiSdiIsisSiIsrirIisrDdiriisrIisiisrirssisisisisisisiSiSisiSisIsisIsIsisiSddiRiisriiiSissiisissiisissiisissdiRiIsrdIriIsriIsIisriRsssIisrirdiRiisrdiriisriisiisrirsssIiSrirSiiSrirIsIsisiSisiSdisisisIsisisisisisddddiriisrisIsIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsisIisrirdiRiisriisissiisissiisissiIsIssiIsiSsiiSiSsiisIssiIsissiisRirisisisisiriisririisriRiIsriIisIssiIsIssdiRiisRiisiisrIrssdiriisriisiisrirssiiSiSsirIisRiisIiSrirsSiisRiriisriRiisrirdisisisdisisisisiSiSdirIisRdiiSiSisisIsisIsisisisIsisisisissiisririisisisSdIriiSrdIisiSiSisisIsisIsisisdiRiisriisiisrirssissdisisIsIsisIsiSddiRiIsrisIsisIsisisisIsiriisrisisisisisiisrirIiSrirIisRirdIiSisisSiriIsrdiisiSisisisdiriisriisiisrirsSdIriiSriIsiiSrIrssiSisiSsdisisiSisisisisisisisisiisrirdDiRiisRiiSisiSiSisisIssiIsririsiSddiriisriisisisisisisisIsIsisIsiSisiSsDiisiSisiSisissiiSririsisdiriisrdiisisisiSiSisiSisIsisIsDiriiSriiSiisrirsSsdisisisisiisrirdiriisrDiIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsisDiriisriIsiisrirssissdiriisrdisiSiSisiSisIsisIsIsisiSdisIsisiisrIriisisisisisissiisrirdiIsIsisIsiSsdiSiSdiriIsrdIisisisiSisisisisisisisisisissiiSrIrisIsdIriiSrDiisiSisiSisisisiSissdiisisissdiriisrdiisIsIsisIsiSisdIrIisriIsiiSrirssisSiisririsisisisiisrirddiIsIsisSdiIsisIsIsissIriiSririisrIriisrdiisisisisisdiriisRiIsiiSriRssdIrIisriIsiiSrirssisIsisisisissdisisiisririiSrIriiSriRdirIiSriisIsisIsisisisIsdiriisriisiisrirsssdiiSiSsdiSisDisiSiSdisdIisiSsdisisiIsrirdiisisisisisisisdirIiSriiSiiSrirSsIssdiIsisSdiisisiSisisisdiriisriisiisrirsSsIisr

Given that the resulting string has no non-printable characters, this verifies that our XOR key has to be correct or at least very close. Looks like it’s time to dive into the esolang hint.

Esolangs

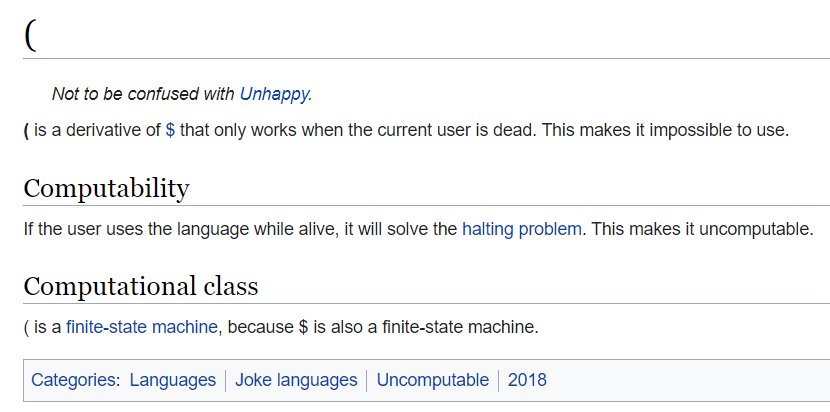

The term “esolang” refers to esoteric programming languages. A very interesting body of programming languages designed not for practical uses as one would expect but usually as a proof-of-concept or to portray a weird interesting idea. The syntax for esolangs is often very odd or very funny with my favorite examples including (:

Or Pikalang, an infamous member of the Brainfuck family of programming languages. It even has its own python package you can install with pip install pikalang!

| Brainfuck | Pikalang | Description |

|---|---|---|

| > | pipi | Move the pointer to the right |

| < | pichu | Move the pointer to the left |

| + | pi | Increment the memory cell under the pointer |

| - | ka | Decrement the memory cell under the pointer |

| . | pikachu | Output the character signified by the cell at the pointer |

| , | pikapi | Input a character and store it in the cell at the pointer |

[ |

pika | Jump past the matching chu if the cell under the pointer is 0 |

] |

chu | Jump back to the matching pika |

Let’s see what a simple “Hello, World!” program looks like in this iconic language

pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pika pipi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pipi pi pi

pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pipi pi pi pi pipi pi pichu pichu pichu pichu ka

chu pipi pi pi pikachu pipi pi pikachu pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pikachu

pikachu pi pi pi pikachu pipi pi pi pikachu pichu pichu pi pi pi pi pi

pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pi pikachu pipi pikachu pi pi pi pikachu ka

ka ka ka ka ka pikachu ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka pikachu pipi pi pikachu

pipi pikachu

Lovely.

Scrolling through the Language List of esolangs at the link provided in the description we see that the Deadfish family of esolangs uses a very similar character set to the characters we find in our decoded one-time-pad which includes only upper and lowercase variations of i, r, s, d as well as an @ symbol. Unfortunately Deadfish languages do not employ @ symbols so we’re going to have to look a little deeper.

Considering the esolang was described saying "Deadfish was originally going to be called fishheads as programming in this language is like eating raw fish heads" we can maybe even consider this a fortunate mistake.

Looking even further we find the Wagon programming language which unfortunately isn’t much simpler. Employing capital and lowercase i, s, p, d, r, and @ this has to be what we were looking for. Going to the table of macros for Wagon we find:

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| i | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which performs o then pushes a 1 onto the stack. |

| I | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which pushes a 1 onto the stack then performs o. |

| s | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which performs o then pops a from the stack then pops b from the stack and pushes b - a. |

| S | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which pops a from the stack then pops b from the stack and pushes b - a then performs o. |

| p | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which performs o then pops a value from the stack and discards it. |

| P | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which pops a value from the stack and discards it, then performs o. |

| d | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which performs o then duplicates the top value on the stack. |

| D | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which duplicates the top value on the stack then performs o. |

| r | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which performs o then pops a value n from the stack, then pops n values from the stack and temporarily remember them, then reverses the remainder of the stack, then pushes those n remembered values back onto the stack. n must be zero or one. |

| R | Takes an operation o and returns an operation which pops a value n from the stack, then pops n values from the stack and temporarily remember them, then reverses the remainder of the stack, then pushes those n remembered values back onto the stack, then performs o. Again, n must be zero or one. |

| @ | Takes an operation o and returns an operation that repeatedly performs o as long as there are elements on the stack and the top element of the stack is non-zero. |

While complex, these operations begin to make sense when you look at how Wagon is designed. Instead of operations that take functions from states to states, operations take functions that take states to states to functions that take states to states. This is known as a second-order concatenative” language. Additionally, program states in Wagon are unbounded stacks (rather typical for stack-based languages) of unbounded integers (why???).

We have a lot of characters in our decoded one-time-pad so I was relieved to see when I scrolled further that some gracious soul had written an optimized Wagon interpreter.

A deep dread sets in and thoughts on how computer science was a mistake begin to flood my mind as I see that the only Wagon interpreter is written in Haskell. sigh Let’s download it nonetheless.

-- Wagon implementation.

--

-- Wagon is a second-order concatenative language by Chris Pressey.

-- See https://esolangs.org/wiki/Wagon for further information.

--

-- Author: Bertram Felgenhauer <[email protected]>

module List where

import Data.Char

import Debug.Trace

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Running Wagon programs.

type Elem = Integer

type Stack = [Elem]

type Op = [Elem] -> [Elem]

parseOp :: Char -> Op -> Op

parseOp c = case c of

'i' -> after opI

'I' -> before opI

's' -> after opS

'S' -> before opS

'd' -> after opD

'D' -> before opD

'p' -> after opP

'P' -> before opP

'r' -> after opR

'R' -> before opR

't' -> after opT

'T' -> before opT

'@' -> while

_ | isSpace c -> id

where

opI, opS, opD, opR, opT :: Op

-- 'i'/'I': push 1

opI ss = 1 : ss

-- 's'/'S': subtract

opS (a : b : ss) = b - a : ss

-- 'p'/'P': pop

opP (_ : ss) = ss

-- 'd'/'D': dup

opD (a : ss) = a : a : ss

-- 'r'/'R': rotate bottom of stack

opR (n : ss)

| 0 <= n && n <= 1,

n' <- fromInteger n,

length ss >= n' =

take n' ss ++ reverse (drop n' ss)

-- 't'/'T': print current stack (extension for debugging)

opT ss = traceShow ss ss

after, before :: Op -> Op -> Op

after = (.)

before = flip (.)

-- '@': while loop

while :: Op -> Op

while o ss

| null ss || head ss == 0 = ss

| otherwise = while o (o ss)

parse :: String -> Op

parse = foldl (flip parseOp) id

run :: Op -> Stack

run = ($ [])

exec :: String -> Stack

exec = run . parse

Using the wonderful Glasgow Haskell Compiler, we run the Wagon interpreter with ghci interpreter.hs, and run our Wagon program like this:

exec "irIiSriiSisSiisIsSiisiSsiiSissiisiSsiisissiisissiisissiisiSsIisiSsiIsriRiS@SSIsIISsISIISSIsIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSIsIiSSIsIIsSISiIsIIRIrSIIsIIpisisIsisisddisiriisrisisisisIsIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsiiSrirdisiSisisisisisisisisisisisiSiSisiSdiIsisSiIsrirIisrDdiriisrIisiisrirssisisisisisisiSiSisiSisIsisIsIsisiSddiRiisriiiSissiisissiisissiisissdiRiIsrdIriIsriIsIisriRsssIisrirdiRiisrdiriisriisiisrirsssIiSrirSiiSrirIsIsisiSisiSdisisisIsisisisisisddddiriisrisIsIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsisIisrirdiRiisriisissiisissiisissiIsIssiIsiSsiiSiSsiisIssiIsissiisRirisisisisiriisririisriRiIsriIisIssiIsIssdiRiisRiisiisrIrssdiriisriisiisrirssiiSiSsirIisRiisIiSrirsSiisRiriisriRiisrirdisisisdisisisisiSiSdirIisRdiiSiSisisIsisIsisisisIsisisisissiisririisisisSdIriiSrdIisiSiSisisIsisIsisisdiRiisriisiisrirssissdisisIsIsisIsiSddiRiIsrisIsisIsisisisIsiriisrisisisisisiisrirIiSrirIisRirdIiSisisSiriIsrdiisiSisisisdiriisriisiisrirsSdIriiSriIsiiSrIrssiSisiSsdisisiSisisisisisisisisiisrirdDiRiisRiiSisiSiSisisIssiIsririsiSddiriisriisisisisisisisIsIsisIsiSisiSsDiisiSisiSisissiiSririsisdiriisrdiisisisiSiSisiSisIsisIsDiriiSriiSiisrirsSsdisisisisiisrirdiriisrDiIsisIsiSisiSiSisisIsisDiriisriIsiisrirssissdiriisrdisiSiSisiSisIsisIsIsisiSdisIsisiisrIriisisisisisissiisrirdiIsIsisIsiSsdiSiSdiriIsrdIisisisiSisisisisisisisisisissiiSrIrisIsdIriiSrDiisiSisiSisisisiSissdiisisissdiriisrdiisIsIsisIsiSisdIrIisriIsiiSrirssisSiisririsisisisiisrirddiIsIsisSdiIsisIsIsissIriiSririisrIriisrdiisisisisisdiriisRiIsiiSriRssdIrIisriIsiiSrirssisIsisisisissdisisiisririiSrIriiSriRdirIiSriisIsisIsisisisIsdiriisriisiisrirsssdiiSiSsdiSisDisiSiSdisdIisiSsdisisiIsrirdiisisisisisisisdirIiSriiSiiSrirSsIssdiIsisSdiisisiSisisisdiriisriisiisrirsSsIisr"

Aaaaaaaaaand it doesn’t work.

*** Exception: List.hs:(48,5)-(50,44): Non-exhaustive patterns in function opR

On the verge of switching my major to Business Development or Communications, I flip back to the description of Wagon macros and continue parsing. With the help of the resident Haskell expert on my team I was able to modify the last six lines of the interpreter from

parse :: String -> Op

parse = foldl (flip parseOp) id

run :: Op -> Stack

run = ($ [])

exec :: String -> Stack

exec = run . parse

to be

parse :: [Char] -> [Op]

parse = scanl (flip parseOp) id

run :: Op -> Stack

run = ($ [])

exec :: [Char] -> [Stack]

exec = map run . parse

This allows us to see the program stack at every point in its operations. With this I was able to narrow down the part of the Wagon code that was causing the problem to just the very first few characters before the @.

Looking more into this, one odd thing that immediately begins to stick out is that in sample programs I found for Wagon, all use cases of the @ while loop have all lowercase characters before the occurence of the @, such as in the simple while loop below:

p@ I I I SII SII

Note: The output of Wagon is simply the stack state at the end of the program, starting from the identity function, which for the case above is just [0, 0]

Seeing as the language does not change capitalization freely there may be some pattern here. In fact, lowercase and uppercase characters represent functions of the same operations but with a different order: lowercase characters first perform the input function and then a set of operations, while uppercase characters first perform a set of operations and then perform their input function. (Thank you Wagon, very cool.)

With our knowledge of XOR we know that by flipping the capitalization of the UTF-8 characters in the key, we are able to flip the capitalization of the resultant character in the decoded plaintext. Going through all the uppercase characters appearing before the @ we find their corresponding index in the key and flip its capitalization to get a resulting proper key of

TobefairyouhavetohaveaveryhighIQtounderstandRickandMorty

Likely guessable, but at least we got learn a little more about Wagon along the way.

Finally, after XORing the hex bytes from the start of the challenge with our new key we get our resulting final program and plug it back into the interpreter.

$ ghci interpreter.hs

GHCi, version 8.6.5: http://www.haskell.org/ghc/ :? for help

[1 of 1] Compiling List ( interpreter.hs, interpreted )

Ok, one module loaded.

*List> exec "iriisriisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisriris@SSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISSISIISIIRIRSIISIIpisisisisisddisiriisrisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisiisrirdisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisdiisissiisririisrddiriisriisiisrirssisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisisddiriisriiisissiisissiisissiisissdiriisrdiriisriisiisrirsssiisrirdiriisrdiriisriisiisrirsssiisrirsiisririsisisisisisdisisisisisisisisisddddiriisrisisisisisisisisisisisisisiisrirdiriisriisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisissiisririsisisisiriisririisririisriiisissiisissdiriisriisiisrirssdiriisriisiisrirssiisissiriisriisiisrirssiisririisririisrirdisisisdisisisisisisdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisisisisisisisissiisririisisissdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssissdisisisisisisisddiriisrisisisisisisisisiriisrisisisisisiisririisririisrirdiisisissiriisrdiisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssdiriisriisiisrirssisisissdisisisisisisisisisisisiisrirddiriisriisisisisisisissiisririsisddiriisriisisisisisisisisisisisisisissdiisisisisisissiisririsisdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirsssdisisisisiisrirdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssissdiriisrdisisisisisisisisisisisisdisisisiisririisisisisisissiisrirdiisisisisissdisisdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisisisisisisissiisririsisdiriisrdiisisisisisisisisissdiisisissdiriisrdiisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssissiisririsisisisiisrirddiisisissdiisisisisissiriisririisririisrdiisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssdiriisriisiisrirssisisisisisissdisisiisririisririisrirdiriisriisisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirsssdiisissdisisdisisisdisdiisissdisisiisrirdiisisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirssissdiisissdiisisisisisisdiriisriisiisrirsssiisr"

[85,68,67,84,70,123,98,117,108,108,121,95,116,104,101,95,109,97,116,104,101,109,97,116,105,99,105,97,110,115,95,115,111,95,116,104,101,121,95,99,97,110,95,103,105,118,101,95,117,115,95,97,115,116,114,111,110,111,109,101,114,115,125]

Yay, an output! Decoding the stack at the end of the Wagon run as an array of decimal characters, we get our final flag of UDCTF{bully_the_mathematicians_so_they_can_give_us_astronomers}