frog-universe

Welcome to Frog Universe!

Can you wander to the flag and back to actually receive it? If you encounter a frog or nebula, it’s game over. Thankfully, frogs will ‘ribbit,’ ‘giggle,’ and ‘chirp,’ and nebulas will ‘light,’ ‘dust,’ and ‘dense.’

We’re also provided with a Python file that runs the game. Let’s go!

Understanding the code

When we run the provided Python file, it allows us to enter keys “w”, “a’”, “s”, “d”

It seems to first give the coordinates of our “flag”, and then the coordinates for where we start (which starts as (2033,0)).

456 1422

[2033 0]

w

[2032 0]

w

[2031 0]

d

[2031 1]

d

[2031 2]

w

[2030 2]

d

[2030 3]

w

[2029 3]

giggle

w

[2028 3]

something happened: ribbity!

try again!

It seems like we can traverse the maze using (as every gamer will know by heart) WASD.

Every time we get close to an obstacle, it gives us a warning if our current player’s position is adjacent to an obstacle. The warning strings are in the _warnings lists:

frog_warnings = ['ribbit', 'giggle', 'chirp']

nebula_warnings = ['light', 'dust', 'dense']

Looking into the conditions on our main game loop:

while m.is_alive == True and not (m.has_flag == True and m.at_exit == True):

It seems like we have to start at (2033, 0), make it to whatever (x_flag, y_flag) they give us in the beginning, then make it back to (2033,0) without running into a bomb and dying.

Hmm… Ok, but now where do we start?

Similarities with other problems in Computer Science

When first messing around with the game and figuring out how to do this, the first thing I thought of was Minesweeper:

We are essentially on one huge grid, and we have to figure out how to explore the grid without running into a bomb. We are given information on how many bombs are around us at each step we take. The difference between this game and our game, though, is that we are not given a whole grid to work with, but instead just a single point in space.

This game also reminds me of another type of Computer Science problem, Maze Solving. The main question is maze solving consists of finding a path from point A to point B given a set of obstacles / nodes and edges. The difference between our game and maze solving though is that we are not given where our obstacles are, all that we know is whether or not we are near a bomb.

Solving Minesweeper

First, let’s take a look at a Minesweeper. Given a Minesweeper board, how can we complete a game without dying?

Note: In Minesweeper, warnings are given to us by looking at all 9 of a square’s neighbors. The game we are working with only tells us if there are any bombs in any of its 4 adjacent neighbors.

Well, first things first: we can click somewhere and uncover all of our “safe squares”.

When we click on a single grid square, we will check if it’s is a bomb or not. If it’s a 0, then we know that all adjacent squares to our initial square also will not have a bomb under them. Thus, we will be able to safely reveal them.

We can then check each of those squares and see if they also have a 0, in which case we would know that their neighbors are also safe to visit.

Continuing this process, we can create a recursive-like algorithm to uncover all our safe points in our gameboard, all the way until we get to an “edge” where only non-zero tiles exist. We will call this method of revealing tiles the “0-neighbor” method.

I’ll go over how we can implement this “recursive-ish” algorithm to reveal squares in the next section, but first I’m going to discuss what to do next after we run out of tiles to find using the “0-neighbor” method and only the “edge” of non-zero tiles exists.

Discovering new safe points using Neighbor Pruning

So now let’s assume we are at the point where we chose our initial position, we have been able to see all the adjacent points to that point and all the adjacent points to the adjacent points of that point (and so on…) that are safe. We are now at the point where we do not have any more bomb-free squares (because the point does not have a 0 square next to it telling us that). What can we do?

Well, there are multiple techniques for figuring out what to do next. For instance, how would a human think – and can we replicate that computationally?

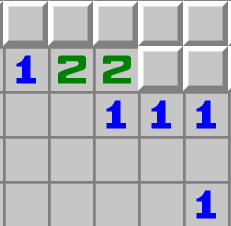

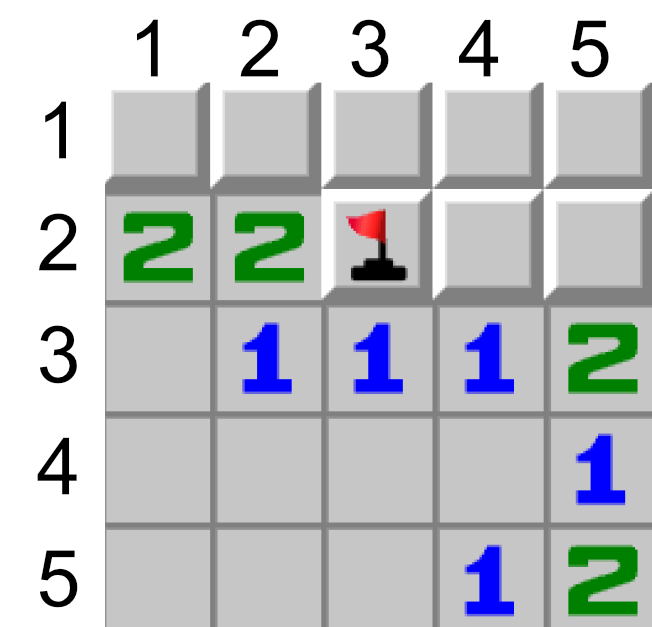

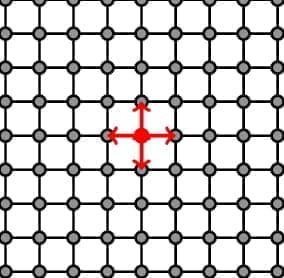

Let’s take a look at this board, as an example. Look at the 1 in the middle. The 1 tells us that there is only one bomb that surrounds the square. If we look at its neighbors, only one of the square’s neighbors is unknown. Since there is only one unknown neighbor and one bomb that surrounds the square, we can say that square has a bomb.

Now we can mark that position as a bomb, and we can check all the neighbors of that bomb to see if there were any other squares we might be able to better understand because of this new information.

I will be referring to the coordinates of these squares as \((y, x)\), where \((1, 1)\) is the top left and \((5,5)\) is the bottom right.

Since we know the position of the bomb is \((2, 3)\), we can check all 8 of its adjacent squares.

\((2, 4)\), \((1, 4)\), \((1, 3)\), \((1, 2)\)

These points are still unknown to us, so let’s not touch them just yet.

\((3, 2)\), \((3,3)\), \((3,4)\)

These points are all marked as a 1, and we now know the location of the bomb that they’re referring to. This means that all other surrounding the 1’s are not a bomb, so we can mark these other adjacent points as safe. We will mark points \((2, 4)\) and \((2, 5)\) as safe. We can also add these coordinates to some type of list to keep track of possible points we can use to recursively discover using our 0-neighbor pruning trick later on.

(2, 2)

Since we now know new information about the bombs surrounding this point, we can check it agian. We now know one of the two bombs that surround this point, but since we still do not know the second bomb we can’t do anything more.

There are some more techniques we can use to try and discover new safe spots, but it turns out the only two we really need to solve our flag are the two described above: Zero-Neighbor and Neighbor-Pruning. So now our next question is, how exactly can we implement this “recursive” discovery algorithm I mentioned earlier? Well, first we will have to dive deep into the realm of Graph Traversal in Computer Science.

Graph Traversal

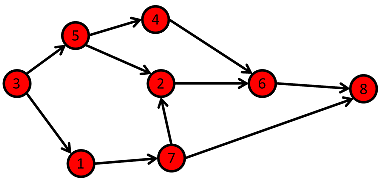

What exactly is a graph? In loose terms, it is simply a collection of nodes connected by edges.

One common problem in computer science is: Given two nodes, how can we find a pathway from one node to the other? For example, if I give you node 3, can you tell me the steps I would need to take to get from point 3 to point 6?

One solution to this problem that computer scientists have found is an algorithm called Breadth-First Search. Here it is, implemented with a queue in Python:

queue = [] #Initialize a queue

def bfs(graph, init_node, goal_node): # function for BFS

# graph = an array which tells us all the edges of a given node

# init_node = node we start off at

# goal_node = node we want to get to

queue.append(init_node)

while queue: # Creating loop to visit each node

m = queue.pop(0)

if m == goal_node:

return True

for neighbour in graph[m]:

queue.append(neighbour)

Note: The above is a very simplified version of Breadth First Search in python, and foregoes some more features that we can add to Breadth First Search, such as the following:

- A visited set to make sure we are not re-visiting nodes that we have already seen

- A way to keep track of the path we are taking. One way we can store this is in an object structure such as

{node: node, path: node[]}.

Applications to Path Finding / Minesweeper

Now that we have the general premise of traversing a graph, how can this help us with Minesweeper?

Well, one of the first things we can do is transform what we can think of as a graph. We can convert our Minesweeper grid into a graph – think of each square as something we can traverse onto, and there will exist 4 edges connecting each square to each of its adjacent neighbors.

To try and get a better intuition on how a breadth-first search algorithm might work with grids, we can look at maze-solving, where we’re given a maze / an array of walls and we need to find our way out.

If you look at the above GIF, you can see how breadth-first search is working. At each of the nodes, you add all of the neighboring nodes to a queue. You visit all of those nodes, and while visiting them you continue to add all of the neighboring nodes’ neighbors to the queue. We then visit all of those nodes, all of those neighboring neighboring …, etc.

You can also see how a pattern emerges with breadth-first search where you tend to search almost “1 layer” at a time. Graph traversal is a huge concept in Computer Science and I will not be going in-depth with all of the different graph traversals in Computer Science, but below are some more examples of popular graph traversals and how they look.

There are also some other ways to traverse a graph. For example, depth first search:

And A* search, which is a highly optimized graph traversal algorithm:

Let’s see if we can now traverse the graph of Minesweeper.

Applying Path Finding to Minesweeper

First, let’s assume our starting point is free of all bombs and warnings (if it is not, we can always restart our Minesweeper game until it is).

We will first traverse to our first spot in our board and add our top, right, left, and bottom spots to our queue (assuming they exist – since the grid does not exist at the bottom and to the left, we won’t add those out-of-bounds points).

We will then go to the next node in the queue. If this node is a 0, then we can safely add the top, right left, and bottom spots into our queue, and continue traversing.

If our node is not a 0, that means it is rather a 1, 2, or 3 (and hopefully not a bomb – otherwise we’re dead!). If we are at a 1, 2, or 3, we can mark this point as a “special point.” The first thing we want to check is if we already know all the locations of the bombs that this node warns us of. So if the node warns us of 2 bombs, and we already know the locations of the 2 adjacent bombs, we can mark the other 2 adjacent points as safe and add them to our queue. If we do not already know the location of the bombs that the node warns us of, then we will not add the neighbors to the queue (to avoid stepping into a bomb), and we will move on. We would also want to remember this point for later on (by storing it in some type of set), to possibly use for our neighbor-pruning technique from earlier.

Note: We will also be keeping track of a seen set to make sure we are not traversing through a point that we have already been to before.

We can go through this cycle over and over again until we get to a point where there are no longer any more spots that we can guarantee to be safe because of our 0-neighbor trick.

Once we run out of neighbors to check with our 0-neighbor trick, we can iterate through all the points we saved in our “special points” set and check to see if any of them qualify for our neighbor-pruning trick from earlier. If they do, we can mark the new points as bombs and update all of that bomb’s neighbors to see if there are any points we can now guarantee to be safe. These points can then be added to our queue, and we can redo our Breadth-First Search on this newly filled queue.

Path Finding Inception

Cool! Now we have a systematic way of finding our way through the game without killing ourselves. We just need to slowly inch our way around the gameboard, checking only the 0-neighboring points – then, after we run out of points to check using that method, we can move on to using the neighbor-pruning points, getting us back to our 0-neighbor method once again. Rinse and repeat until we finish our board.

But there is one oversight that I did not address in the above statement. We have a general idea now of how we can slowly traverse our whole graph – but how would we traverse through the game itself? For example, let’s say I’m at node (40,30), and the next point in the queue tells me to go to (15,23). If you remember earlier when I was demonstrating the program, all I can enter is WASD. I need to somehow calculate the correct WASD moves to get from (40,30) to (15,23) without stepping on a bomb and killing myself.

As it turns out, we can again still use Breadth First Search to figure out where to go next. This is almost the same problem we talked about originally: given a point A and a point B and a graph G, find a path from A to B.

TL;DR

So in summary, this is what we would need to code:

- Keep track of the entire gameboard, making sure to keep track of the state of each square.

- Some of the different states that we should keep track of include:

- B = Bomb

- 0 = Safe Spot

- ? = Unknown

- 1 = 1 neighboring bomb

- 2 = 2 neighboring bombs

- 3 = 3 neighboring bombs

- Some of the different states that we should keep track of include:

- Start at our initial position (which in the game is (2033, 0)), and slowly Breadth-First Search through all of the safe spots (which we are checking for using our 0-neighbor method) in our gameboard

- In our breadth-first search we will keep track of:

- A queue of nodes to visit next

- A set of special points that we can refer to later on to use for our neighbor-pruning technique

- A set of seen nodes that we use to keep track of the nodes we have already visited, so we don’t re-visit nodes we’ve already been to

- In our breadth-first search we will keep track of:

- During our main BFS of the entire gameboard, we will need to calculate the WASD moves to get from one node to another.

- So we will have another helper function called

go_to_location(matrix, start, end)which will return an array of chars consisting of ‘w’, ‘a’, ‘s’, ‘d’, which we can send to the server to get us to where we want to go. - We will be finding the correct pathway for us to take / the WASD moves to take using another BFS algorithm.

- So every iteration in our overall BFS algorithm, we will be using another mini BFS algorithm to get from one point to another.

- After we traverse to that point, the server will give us an output which we can parse into the number of warnings that we currently have at our position.

- So we will have another helper function called

- After we run out of positions with our 0-neighbor trick (that is, once our queue of nodes to visit next is empty), we can move on to our set of special points. We can now check that set to see if we can find any more new nodes that we can add to our queue using our neighbor-pruning technique.

- So to implement this technique, we will iterate through every point in the

special_pointsset and see if the number of unknown neighbors equals the number of warnings for any of our special points. If it does, we can update all of the unknown positions as bombs and recheck to see if that gives us any new information about which spots are safe.

- So to implement this technique, we will iterate through every point in the

Now that we know the technique, let’s code it!

Wait wait wait, before we code it… let’s take out some pen and paper, and leetcode interviewing-style check our time-complexity first.

O(Error 408 Request Timeout)

Let’s do some quick math.

We have a 2000 by 2000 grid, so we have approximately \(4 * 10^6\) different grid positions to check. Each grid position to check might take ~5 moves to move from one position to another (the # of moves gets bigger as the amount of the grid we have explored expands).

So we will send ~2*10^7 different moves to our game console. And since we have to go to the flag and back we have to multiply this number by 2, so in total, we will have to make \(~10^8\) different moves.

Each move takes approximately 0.01 seconds to make (and that’s with perfect conditions). So in total, it would take ~ 10^8 * 10^-2 = 10^6 seconds to finish our whole traversal, which is 1000000 seconds. or 277 hours.

Sadly, this competition only lasts 48 hours, so it seems like our current algorithm might not work. So now, like every interviewer would ask: “Can we find a more efficient solution?”

Looking For Optimal Graph Traversals

One thing that might help us is looking back at the visualization of our graph traversal, and seeing if there is anything we could do to optimize it.

As you can see, currently, our Breadth-First Search expands out as a circle. Every single whole iteration essentially adds another layer to the shell of the area it has searched. While this might be useful in some problems, in our application, it gives us a lot of wasted moves. We are making quite a lot of moves in the opposite direction of where we want to go.

It seems we would be able to speed up our time-complexity quite a bit by being more selective with our choice of which node to visit next, instead of exploring the whole graph. We could, for instance, choose the closest point in our queue to our target. This will create a more targeted approach to our graph traversal instead of just spraying everywhere.

This algorithm is called Greedy Best First Search, and here is how it looks visualized:

As you can see, instead of extending out spherical shells, this algorithm works more like a directed shotgun, by only choosing points that get it closer to its target.

One interesting observation is that when this algorithm runs into a wall, it does still use the spherical-shell-like method. The reason for this is that the Best First Search method works almost exactly like the Breadth First Search Method – the only difference is that instead of a queue, we use a Priority Queue. Priority queues are very similar to queues – the only difference is that when adding a new element, instead of it just adding it to the back of the queue, the priority queue keeps itself sorted according to some “weight” metric. Thus, the next element to be “popped” out won’t be the earliest element put in, but instead the element with the lowest weight. In our case, we can make our weight the Euclidian Distance between the current node and our goal node. We can calculate this with good ol’ Pythagoras Theorem: \(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\).

We will also need to tweak our neighbor-pruning technique a little to make sure we don’t “bubble back” too much. These two changes will tremendously improve our runtime, and will allow us to use a much more directed approach instead of just exploring the entire graph. The number of positions we have to check is reduced from 10^6 to only ~10^3, turning our 277 hours into a much more manageable 20 minutes.

The Code

We finally have a complete description of our problem and solution. Now we just have to code it.

I’m not going to lie, this was a pain to program. But that’s okay – after 5 hours of banging my head into the keyboard, we finally got it to work. Below is the code that got us the flag:

from pwn import *

import numpy as np

from enum import Enum

from collections import deque

from heapq import heappush, heappop

## Globals:

SIZE = 2034

# declare cell enum (state)

class Cell(Enum):

SAFE_SPACE = 0

UNKNOWN = -1

BOMB = -2

ONE_BOMB = 1

TWO_BOMBS = 2

THREE_BOMBS = 3

# Directions to Instructions

class Directions(Enum):

NORTH = 'w'

EAST = 'd'

SOUTH = 's'

WEST = 'a'

## Util Functions:

def getAllAdjPts(coord):

dxdy = [(0,1), (0, -1), (1,0), (-1,0)]

adjPts = []

for dx, dy in dxdy:

adjPts.append((coord[0] + dx, coord[1] + dy))

return adjPts

def distToFlag(coord):

(y,x) = coord

return abs(x-flag_x)+abs(y-flag_y)

def addToStack(heap,coord):

heappush(heap,(distToFlag(coord),coord))

def range_check(position):

return position[0] > -1 and position[0] < SIZE and position[1] > -1 and position[1] < SIZE

def print_surrounding(maze, position):

# pass

for i in range(-10, 10):

for j in range(-10, 10):

if i == 0 and j == 0:

print('P', end=' ')

else:

if range_check(position + np.array([i, j])):

charToPrint = maze[position[0]+i][position[1]+j]

if charToPrint == -1:

charToPrint = "?"

if charToPrint == -2:

charToPrint = "B"

print(charToPrint, end=' ')

else:

print('x', end=' ')

print()

## I/O Functions:

def get_user_coordinate():

# receive response

try:

i = 0

print("waiting for recv")

time.sleep(0.01)

i = 0

while not r.can_recv():

time.sleep(0.01)

i += 1

if i > 100:

r.interactive()

raw_response = r.recv()

response = str(raw_response)[2:-3].split('\\n')

print('receive this: ', response)

unparsed_string = response[0]

y, x = [int(x) for x in unparsed_string[1:-1].split()]

return y, x, len(response)

except:

print('something wrong with this response: ', raw_response)

exit()

def num_of_warnings_at_end(instructions):

num_of_bomb = -1

for i in instructions:

# execute the instruction

print("sending",i)

r.sendline(i)

print("about to get user coord in num_warnings_at_end")

user_y, user_x, length_of_response = get_user_coordinate()

num_of_bomb = length_of_response - 1

return num_of_bomb

# r = remote('pwn.chall.pwnoh.io', 13380)

r = process(argv=["python3", "maze.py"])

# r.interactive()

# get the position of the flag

flag_pos = str(r.recvline())[2:-3].split(' ')

flag_y = int(flag_pos[0])

flag_x = int(flag_pos[1])

print('This is coordinate of flag (y, x): ', flag_y, flag_x)

get_user_coordinate()

# Main Solver

def main_solve():

seen = set()

matrix = np.zeros((SIZE, SIZE), dtype=int)

matrix.fill(Cell.UNKNOWN.value)

next_visit_stack = []

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(2032,0))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(2033,1))

special_points_set = set()

current_cordd = (2033, 0)

# just make two points good

matrix[2033][0] = 0

matrix[2033][1] = 0

while True:

while len(next_visit_stack) != 0:

# get next coordinate to visit

_, coord = heappop(next_visit_stack)

# if we have seen this coordinate before, skip

if coord in seen or not range_check(coord):

continue

# If this coord is our goal coord, then traverse to this coord and collect the flag

# After doing that, traverse back to our starting position (2033, 0) and we should have our flag!

if coord[0] == flag_y and coord[1] == flag_x:

go_to_location(matrix, current_cordd, coord)

go_to_location(matrix, coord, (2033,0))

r.interactive()

return

# If this coord is a bomb, skip it.

if matrix[coord[0]][coord[1]] == Cell.BOMB.value:

continue

# If neither of the above conditions are satisfied, we will traverse this coordinate

# Mark it as visited

seen.add(coord)

print_surrounding(matrix, coord)

# go to our new cordd

numOfWarnings = go_to_location(matrix, current_cordd, coord)

print("Number Of Warnings at above loc: " + str(numOfWarnings))

current_cordd = coord

# If this is a 0 Coord, all neighbors are safe to visit

if(numOfWarnings == 0):

matrix[coord[0]][coord[1]] = Cell.SAFE_SPACE.value

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0] - 1, coord[1]))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0] + 1, coord[1]))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0], coord[1] + 1))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0], coord[1] - 1))

# If this is not a Zero Coord, we have to be cautious with traversing any of this coord's neighbors

# So we will not immeditly add its neighbors to our stacktovisit

elif numOfWarnings >= 1:

# This will check if we already know all the bombs that this coord is talking about

for adjCoord in getAllAdjPts(coord):

if not range_check(adjCoord):

continue

if matrix[adjCoord[0]][adjCoord[1]] == Cell.BOMB.value:

numOfWarnings -= 1

# If we do, then we can safely add all the neighbors to our stacktovisit, if not we will not

if numOfWarnings == 0:

matrix[coord[0]][coord[1]] = Cell.SAFE_SPACE.value

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0] - 1, coord[1]))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0] + 1, coord[1]))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0], coord[1] + 1))

addToStack(next_visit_stack,(coord[0], coord[1] - 1))

# update the value we have for this coord

matrix[coord[0]][coord[1]] = numOfWarnings

# add this into our special points list as to check for neighbor-pruning later on

special_points_set.add(coord)

# Now implementing neighbor pruning technique

for special_cord in special_points_set.copy():

if matrix[special_cord[0]][special_cord[1]] == Cell.SAFE_SPACE.value:

if special_cord in special_points_set:

special_points_set.remove(special_cord)

continue

# we will be checking all special points to see if we can find

# a point where the total adjacent places of unknowns = num of warnings (such that all unknowns = bombs)

# Check # of Unknowns adjacent to this special point

numOfUnknowns = 0

unknownCoords = []

for newcord in getAllAdjPts(special_cord):

if not range_check(newcord):

continue

if matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] == Cell.UNKNOWN.value:

numOfUnknowns += 1

unknownCoords.append(newcord)

# If the number of unknowns is equal to the number of warnings, then we can safely assume that all unknowns are bombs

if numOfUnknowns == matrix[special_cord[0]][special_cord[1]]:

## WE KNOW WHERE OUR BOMBS ARE!!!!

# first step is replace our matrix val

# second step is to check all surrounding special points

for bombCoord in unknownCoords:

# first step

matrix[bombCoord[0]][bombCoord[1]] = Cell.BOMB.value

# second step (check all surrounding special points)

for newcord in getAllAdjPts(bombCoord):

if not range_check(newcord) or matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] == Cell.UNKNOWN.value \

or matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] == Cell.BOMB.value or matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] == Cell.SAFE_SPACE.value:

continue

# if this is a point which shows we have only one bomb,

# then we now know the bomb that caused the warning

# we can now safely ignore this warning and now start traversal from here.

if matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] == Cell.ONE_BOMB.value:

matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] = Cell.SAFE_SPACE.value

addToStack(next_visit_stack,newcord)

if newcord in seen:

seen.remove(newcord)

special_points_set.remove(newcord)

else:

matrix[newcord[0]][newcord[1]] -= 1

if len(next_visit_stack) == 0:

print("You have no other places in the stack to visit")

break

# This function will find the WASD moves to get from start to end and then send those moves to the server

# It will return the number of warnings it has found at the grid it traversed to

# This works using BFS

def go_to_location(matrix, start, end):

DIRS = [-1, 0, 1, 0, -1]

DIR_MAP = {

0: "w",

1: "d",

2: "s",

3: "a"

}

queue = deque([(start, [])])

visited = set(start)

while queue:

curr_loc, curr_path = queue.popleft()

curr_y, curr_x = curr_loc

if curr_loc == end:

print("goToLocation ", start, end, curr_path)

return num_of_warnings_at_end(curr_path)

for i in range(4):

new_y = curr_y + DIRS[i]

new_x = curr_x + DIRS[i+1]

if range_check((new_y, new_x)) and (int(matrix[new_y][new_x]) not in [Cell.BOMB.value, Cell.UNKNOWN.value] or (new_y, new_x) == end):

if (new_y, new_x) not in visited:

visited.add((new_y, new_x))

queue.append(((new_y, new_x), curr_path + [DIR_MAP[i]]))

print('No traversal path found')

main_solve()

And here’s some sample output:

goToLocation (17, 51) (17, 50) ['a']

sending a

about to get user coord in num_warnings_at_end

waiting for recv

receive this: ['[17 50]']

Number Of Warnings at above loc: 0

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 1 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 1 0 1 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 1 0 0 0 1 ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? B 0 0 0 0 0 1 ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0 0 P B 0 0 1 ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0 0 0 ? 0 1 ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? 0 B 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? 0 0 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? 0 0 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? B 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? B 0 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? 0 0 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

You can find the full output for the program on a sample grid of 100x100 here! I highly recommend checking out this link and scrolling through the graph to see how it works. You’ll be able to see the snake-like features of the traversal, as well as all of the bombs. You can also view how the graph looks from the player’s perspective and each point in its journey (a major lifesaver for debugging).

Conclusion

Thank you to Abi, Zi, and Sam for helping me write the program. This was a painful CTF challenge but it was really fun, and it was satisfying to be able to finally get the flag. Graph traversal is an incredibly useful technique in Computer Science, and this challenge was a great way for me to test my graph theory and programming skills.