crispyr

Rust is wonderful to write, but reversing it is quite the challenge.

Luckily, this became the first Rust challenge I solved, and I learned a lot!

Setup

We’re provided with a single binary crispyr. When we run it, we get a long prologue. Then, we’re asked to find a DNA sequence that expresses a random trait that changes every single time:

Find a DNA sequence that expresses this trait: “fBVTgMiFO4IsuqvUiAop3m8iPLkSGIbxbb5jHwDDAPtQmdHZGRauKwyypaMgL9yo”

If we just enter a random string, we’re greeted with

The lifeform fizzles out and dies… RIP lil Brutus.

Since it mentioned DNA, we tried entering one of every single DNA base: ACGT

Produced trait: ÿ

However, if we tried entering more than one of one base, such as AACGT, we would get the error mentioned before. In addition to this basic test, we tried changing the order of the bases, which yielded a different trait every time.

From this, we concluded that we need to enter a combination of bases, and the number/order of each base matters.

What’s a Valid Sequence?

The decompilation Ghidra provided was very complex, as expected of a Rust binary.

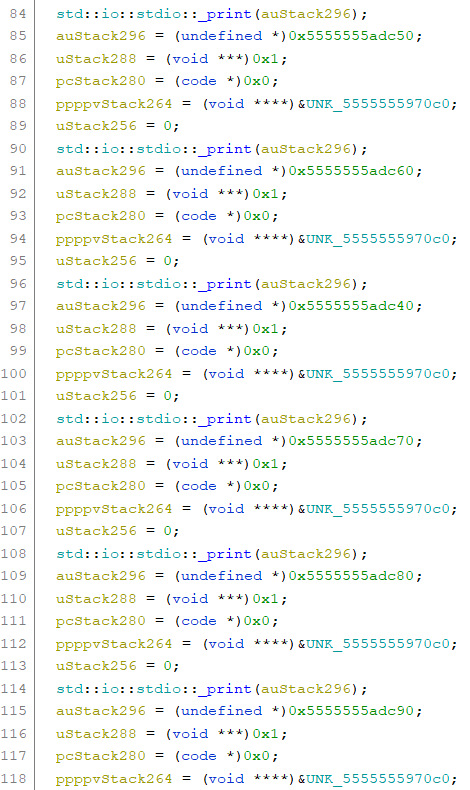

The first 100 or so lines appear to just be the prologue printing due to the recurring std::io::stdio::_print call. Ghidra wasn’t able to find the strings, so the decompilation looked terrible.

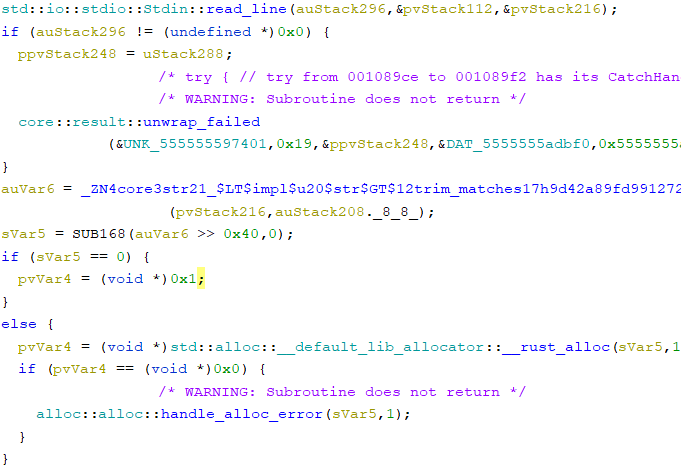

I kept looking, trying to find any place where it was reading input. Eventually, I found std::io::stdio::Stdin::read_line:

I wasn’t too sure what the following code did, but I just chose to ignore it, hoping it was nothing important.

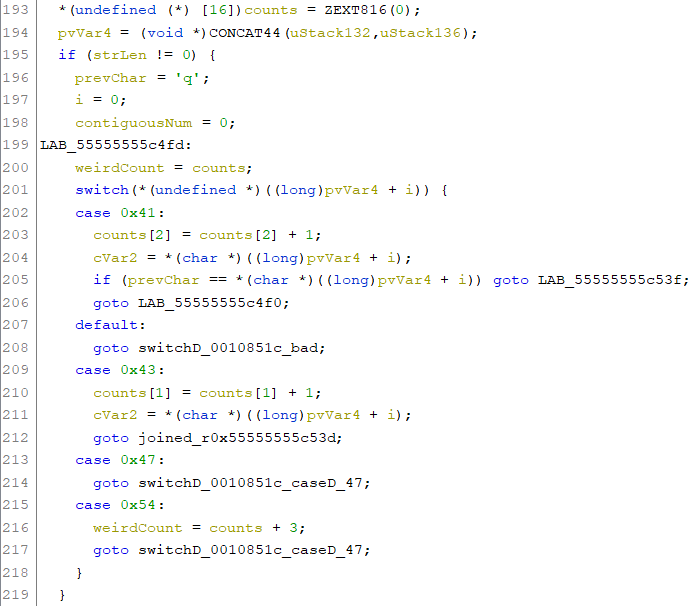

Eventually, I came across a switch statement, with cases for 0x41, 0x43, 0x47, and 0x54. That’s ASCII for A, C, G, and T! This must be where the string is parsed. It seemed like pvVar4 had the string and i was an index to get a specific character. I quickly verified that this was the case using GDB.

Ghidra was correctly able to identify the switch, but the code was not perfect, with a bunch of annoying gotos and random labels everywhere. In the end, though, I was able to reverse it, and I discovered that this was the code to verify that a given DNA sequence was valid. I came up with the following rules:

- Can’t have more than 3 of the same characters in a row

- count of G = C

- count of A = T

Trait Generation

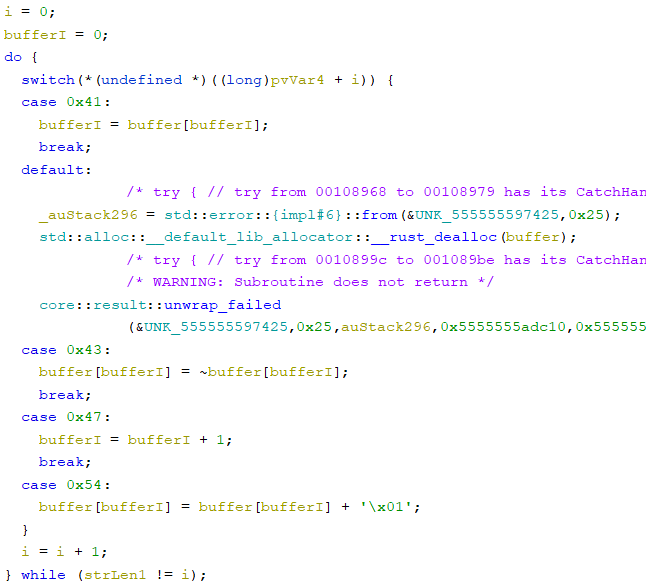

Now, I know how to always produce a trait. What was left was figuring out how a trait was produced. I kept scrolling, and then I found another switch! Just like before, it was iterating through the string.

This one was simpler, and it was just modifying a buffer. The buffer was 0x100 bytes large and was zero-initialized.

Eventually, I was able to figure out how each character modified this buffer. It was some sort of state machine:

- A:

i = buffer[i] - C:

buffer[i] = ~buffer[i] - G:

i++ - T:

buffer[i]++

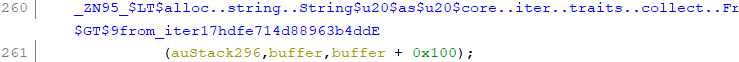

The last step was to figure out how this buffer was used to create the trait. I noticed that immediately after the loop, a very descriptively-named function was called and was passed in the buffer contents

It had been mangled out of recognition. I looked online for a rust demangler, and I found rustfilt, which produced a much more readable rust function name

<alloc::string::String as core::iter::traits::collect::FromIterator<char>>::from_iter

The function just converts an iterator of character bytes into a unicode String. One weird thing I found from testing was that if the bytes aren’t a valid UTF-8 string, it would do some weird transformation and produce a string that had a different byte representation. However, if the input bytes were all valid ASCII, the output string was as expected. Luckily, the random trait provided to us was simple ASCII.

The Final Steps

The last thing I needed to do was figure out an input string that would produce the trait we were asked to produce.

My first instinct was to use a combination of Ts (which would increment the current cell in the buffer) and Gs (which would increment the index) to set up the buffer to have all the correct ASCII bytes, leading to this code.

payload = ""

for i, c in enumerate(trait):

for i in range(c):

payload += "T"

payload += "C"

payload += "C"

payload += "G"

However, I wasn’t sure how to fulfill the rules I had discovered above. As a reminder, here are the rules:

- Can’t have more than 3 of the same characters in a row

- count of G = C

- count of A = T

So I asked the rest of the team for help. Ben instantly figured out that 2 Cs were essentially a NOP, and we could use those to separate our increments. This would fulfill Rule 1. However, neither of us was sure how to fulfill Rules 2 or 3.

After giving it some more thought, I realized that the A and G commands don’t actually modify the buffer at all. As long as the number of Gs and Ts were greater than the number of As and Gs, I could just add the As and Gs in a specific order to get the counts to match. With that out of the way, the last problem to solve was to figure out how to print out the As and Gs so that they met Rule 1.

I thought about it for a while, but my brain got fried. Instead of doing the thinking myself, is there a way I can just let my code figure it out? MATH! I knew that there were always going to be more Gs than Ts, so that means there will always be more Gs than As. The problem boils down to figuring out how I can combine sequences of AG, AGG, and AGGG. From this, I came up with this system of equations. Each variable represents the number of times each type of sequence would occur:

3 * a + 2 * b + c = NUM_A

a + b + c = NUM_G

I discovered sympy, which can solve systems of equations with multiple solutions, and I used it in my code. I couldn’t figure out a way to constrain the variables to be greater than 0, which would’ve made everything automatic, but I compromised by requiring the user to enter the value for a single variable (which is very easy to do given the solution sympy provides) and substitute that in to compute the other variables.

a, b, c = sympy.symbols(["a", "b", "c"])

system = [

sympy.Eq(3 * a + 2 * b + c, num_extra_g),

sympy.Eq(a + b + c, num_extra_a),

]

soln = sympy.solve(system, [a, b, c])

print(soln)

actual_c = int(input())

a = soln[a].subs(c, actual_c)

b = soln[b].subs(c, actual_c)

c = actual_c

for num, count in zip([3, 2, 1], [a, b, c]):

for _ in range(count):

payload += "G" * num

payload += "A"

With that, I got the flag: buckeye{b10l091c41_c0mpu73r5_4r3_c0013r_7h4n_ur5}!

Here’s my full code:

from pwn import *

from collections import Counter

import sympy

p = remote("pwn.chall.pwnoh.io", 13376)

# p = process("./crispyr")

p.recvuntil(b"trait: ")

trait = p.recvline(keepends=False)[1:-1]

payload = ""

for i, c in enumerate(trait):

for i in range(c):

payload += "T"

payload += "C"

payload += "C"

payload += "G"

counter = Counter(payload)

num_extra_a = counter["T"]

num_extra_g = counter["C"] - counter["G"]

assert num_extra_a * 3 >= num_extra_g

# 3 * a + 2 * b + c = NUM_A

# a + b + c = NUM_G

a, b, c = sympy.symbols(["a", "b", "c"])

system = [

sympy.Eq(3 * a + 2 * b + c, num_extra_g),

sympy.Eq(a + b + c, num_extra_a),

]

soln = sympy.solve(system, [a, b, c])

print(soln)

actual_c = int(input())

a = soln[a].subs(c, actual_c)

b = soln[b].subs(c, actual_c)

c = actual_c

for num, count in zip([3, 2, 1], [a, b, c]):

for _ in range(count):

payload += "G" * num

payload += "A"

p.sendline(payload.encode())

p.interactive()