Guardians of the Kernel

Kernel can be a scary word. That’s alright though because we have an SMT solver on our team.

It’s just a warmup but with another layer which is the kernel.

Looking at the Problem

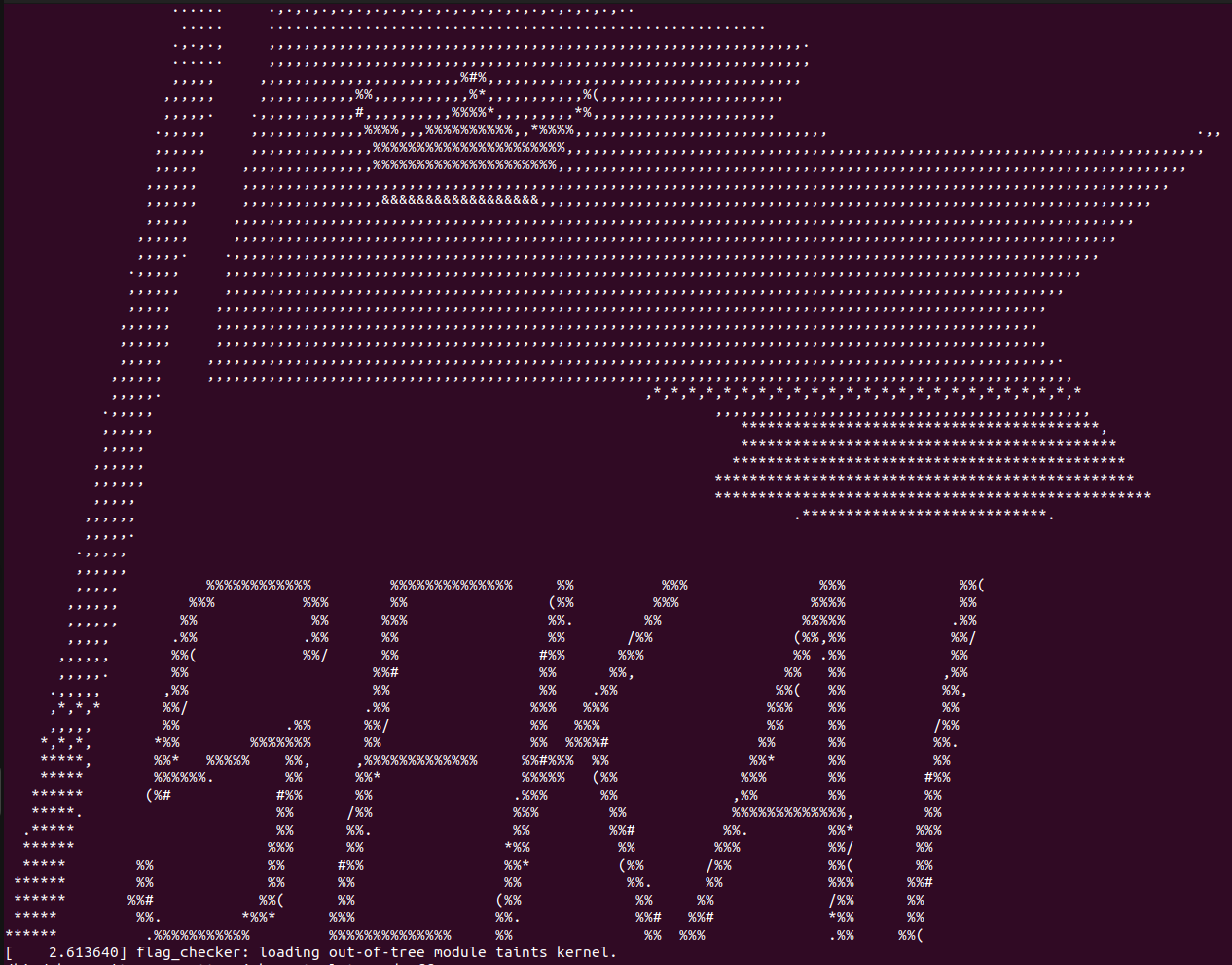

We are provided with a zip file dist.zip containing a custom kernel bzImage and a compressed initramfs.cpio.gz. Let’s start by trying to run this kernel in an emulator like qemu:

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -kernel bzImage

Looks like we get an

Looks like we get an Unable to mount root fs error since there’s no init binary to run. To fix this, let’s try loading the initramfs file we’ve been provided. (Make sure to create a copy of your initramfs.cpio.gz file; this will be necessary later.)

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -kernel bzImage -initrd initramfs.cpio.gz

You can also run it without opening a new window:

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -kernel bzImage -initrd initramfs.cpio.gz -nographic -append "console=ttyS0"

Nice! Looks like we’ve got everything set up. Based off of the warning message, we can run lsmod and see what kernel modules are loaded.

/ # lsmod

flag_checker 16384 0 - Live 0xffffffffc022e000 (O)

This looks like what we’re looking for. It’s possible now to interface with the kernel module, but instead I’m going to try and statically analyze it.

Static Reversing

Going back to our directory with the initramfs.cpio.gz file we can extract the initramfs with:

$ mkdir initramfs

$ cd initramfs

$ gzip -d ../initramfs.cpio.gz

$ cpio -idm < ../initramfs.cpio

You’ll now have a directory with the contents of initramfs:

$ ls

bin etc flag_checker.ko home init linuxrc proc root sbin sys usr

If you look at the init file you can see where the kernel module is loaded with insmod flag_checker.ko. Regardless, let’s load the kernel module into binja and start analyzing.

00000060 int64_t device_ioctl(int64_t arg1, int32_t arg2)

00000060 {

0000006a if (arg2 == 0x7001)

00000065 {

000000e4 if (data_574 == 0)

000000e2 {

00000083 label_83:

00000083 return 0;

00000083 }

000000fa if (_copy_from_user(0x8e0) != 0)

000000f7 {

00000236 label_236:

00000236 return -0xe;

00000236 }

00000100 data_8e7 = 0;

00000107 char* rax_5 = &buffer;

0000011e while ((*(int8_t*)rax_5 - 0x30) <= 9)

0000011b {

00000124 rax_5 = &rax_5[1];

0000012b if (0x8e7 == rax_5)

00000128 {

0000014a uint64_t rax_9 = ((uint64_t)(ROLD(((RORD((buffer * 0x193482ba), 0xf)) * 0x59d87c3f), 0xb)));

00000180 int32_t rax_17 = (((RORD(((((uint32_t)(*(int8_t*)data_8e4)) ^ ((((uint32_t)data_8e6) << 0x10) ^ (((uint32_t)*(int64_t*)((char*)data_8e4 + 1)) << 8))) * 0x193482ba), 0xf)) * 0x59d87c3f) ^ ((((int32_t)(rax_9 << 3)) - rax_9) + 0x47c8ac62));

0000018c int32_t rax_20 = (((rax_17 >> 0x10) ^ (rax_17 ^ 7)) * 0x764521f9);

00000199 int32_t rax_22 = ((rax_20 ^ (rax_20 >> 0xd)) * 0x93ac1e76); // {"NU"}

000001ab if ((rax_22 ^ (rax_22 >> 0x10)) == 0xf99c821)

000001a6 {

000001b1 /* tailcall */

000001b1 return device_ioctl.cold();

000001b1 }

000001a6 break;

000001a6 }

0000014a }

0000011b goto label_83;

0000011b }

00000071 if (arg2 != 0x7002)

0000006c {

00000089 if (arg2 != 0x7000)

00000084 {

000002e1 printk(0x367);

000002e8 return 0;

000002e8 }

000000a3 if (_copy_from_user(0x8e0) != 0)

000000a0 {

000000a3 goto label_236;

000000a3 }

000000be if ((buffer == 0x414b4553 && data_8e4 == 0x7b49))

000000b5 {

000000c7 printk(0x31b);

000000d1 data_574 = 1;

000000db return 1;

000000db }

000000a9 goto label_83;

000000a9 }

0000007b if (data_578 == 0)

00000079 {

0000007b goto label_83;

0000007b }

000001c2 void* rax_25 = _copy_from_user(0x8e0);

000001c7 void* rdx_13 = rax_25;

000001cd if (rax_25 != 0)

000001ca {

000001cd goto label_236;

000001cd }

000001e7 do

000001e7 {

000001d9 *(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e0) = (*(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e0) + (((int8_t)(!rdx_13)) * *(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e1)));

000001df rdx_13 = ((char*)rdx_13 + 1);

000001df } while (rdx_13 != 0xc); // {"GNU"}

00000217 if (((*(int64_t*)buffer) == 0x788c88b91d88af0e && (data_8e8 == 0x7df311ec && data_8ec == 0)))

00000210 {

00000224 printk(0x350);

0000022e return 1;

0000022e }

000001f3 goto label_83;

000001f3 }

It looks like the data is being checked in 3 distinct parts, so let’s start with the most easily digestible ones.

Part 1

if (arg2 != 0x7002)

{

if (arg2 != 0x7000)

{

printk(0x367);

return 0;

}

if (_copy_from_user(0x8e0) != 0)

{

goto label_236;

}

if ((buffer == 0x414b4553 && data_8e4 == 0x7b49))

{

printk(0x31b);

data_574 = 1;

return 1;

}

goto label_83;

}

label_83points to a false return so we want to avoid jumping there with our input for all the parts.

This part specifically looks like it’s doing a direct value comparison which makes it easy for us. buffer == 0x414b4553 and data_8e4 == 0x7b49 decoded give us part 1 of the flag SEKAI{ after swapping endianness of the hex bytes.

Part 3

Let’s procrastinate on some of the longer segments and take a look at the ending portion.

do

{

*(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e0) = (*(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e0) + (((int8_t)(!rdx_13)) * *(int8_t*)((char*)rdx_13 + 0x8e1)));

rdx_13 = ((char*)rdx_13 + 1);

} while (rdx_13 != 0xc); // {"GNU"}

if (((*(int64_t*)buffer) == 0x788c88b91d88af0e && (data_8e8 == 0x7df311ec && data_8ec == 0)))

{

printk(0x350);

return 1;

}

goto label_83;

Cleaning up the decomp a bit we can get it down to some more readable pseudocode.

do

{

[i + 0x8e0] = [i + 0x8e0] + (!i) * [i + 0x8e1];

i = (i + 1);

} while (i != 0xc);

if ((buffer == 0x788c88b91d88af0e && (data_8e8 == 0x7df311ec && data_8ec == 0)))

{

printk(0x350);

return 1;

}

goto label_83;

It appears that this is looping over the buffer values and adding the value at an index to the bitwise NOT of the index, multiplied by the next consecutive value. Converting this to pseudo python we have something along the lines of:

buffer = []

newBuffer = []

for i in range(0xc):

newBuffer.append(buffer[i] + (~i & 0xFF) * buffer[i + 1])

if newBuffer[0:8] == 0x788c88b91d88af0e and newBuffer[8:12] == 0x7df311ec

We need to find an input buffer that will result in the ending newBuffer matching the conditions provided by the final if statement. Thankfully we don’t have to setup equations or do this ourselves! With the trusty power of a tool like Z3 or some other SMT solver we can “add” our constraints and have it find the necessary inputs for us.

CTF rev players discovering symbolic execution pic.twitter.com/n0G5jBdIQG

— faulty *ptrrr (@0x_shaq) July 6, 2023

from z3 import *

buffer = []

for i in range(0xd):

buffer.append(BitVec(f"buf{i}", 8))

s = Solver()

newBuffer = []

for i in range(0xc):

newBuffer.append(buffer[i] + (~i & 0xFF) * buffer[i + 1])

first = Concat(newBuffer[7], newBuffer[6], newBuffer[5], newBuffer[4], newBuffer[3], newBuffer[2], newBuffer[1], newBuffer[0])

s.add(first == 0x788c88b91d88af0e)

second = s.add(Concat(newBuffer[0xb], newBuffer[0xa], newBuffer[9], newBuffer[8]) == 0x7df311ec)

print(s.check())

m = s.model()

print(m)

inp = b""

for b in buffer:

inp += m[b].as_long().to_bytes(1, "big")

print(inp)

This gets us our third part of the flag: SEKAIPL@YER}

Part 2

For the middle and final part looks like we need to reverse this segment:

if (arg2 == 0x7001)

{

if (data_574 == 0)

{

label_83:

return 0;

}

if (_copy_from_user(0x8e0) != 0)

{

label_236:

return -0xe;

}

data_8e7 = 0;

char* rax_5 = &buffer;

while ((*(int8_t*)rax_5 - 0x30) <= 9)

{

rax_5 = &rax_5[1];

if (0x8e7 == rax_5)

{

uint64_t rax_9 = ((uint64_t)(ROLD(((RORD((buffer * 0x193482ba), 0xf)) * 0x59d87c3f), 0xb)));

int32_t rax_17 = (((RORD(((((uint32_t)(*(int8_t*)data_8e4)) ^ ((((uint32_t)data_8e6) << 0x10) ^ (((uint32_t)*(int64_t*)((char*)data_8e4 + 1)) << 8))) * 0x193482ba), 0xf)) * 0x59d87c3f) ^ ((((int32_t)(rax_9 << 3)) - rax_9) + 0x47c8ac62));

int32_t rax_20 = (((rax_17 >> 0x10) ^ (rax_17 ^ 7)) * 0x764521f9);

int32_t rax_22 = ((rax_20 ^ (rax_20 >> 0xd)) * 0x93ac1e76); // {"NU"}

if ((rax_22 ^ (rax_22 >> 0x10)) == 0xf99c821)

{

/* tailcall */

return device_ioctl.cold();

}

break;

}

}

goto label_83;

}

Thankfully we can apply the same process as before and use an SMT solver to set constraints on the output and solve for the corresponding input. My script for this section looked something like this:

from z3 import *

s = Solver()

while True:

buffer = []

for i in range(7):

buffer.append(BitVec(f"buf{i}", 8))

s.add(0x21 <= buffer[i], buffer[i] <= 0x7e)

s.add(And(buffer[0] < 0x39, buffer[1] < 0x39, buffer[2] < 0x39, buffer[3] < 0x39, buffer[4] < 0x39, buffer[5] < 0x39, buffer[6] < 0x39))

buf4 = ZeroExt(24, buffer[4])

buf5 = ZeroExt(24, buffer[5])

buf6 = ZeroExt(24, buffer[6])

eax = Concat(buffer[3], buffer[2], buffer[1], buffer[0]) * 0x193482ba

ecx = buf6

ecx <<= 0x10

eax = RotateRight(eax, 0xf)

eax *= 0x59d87c3f

eax = RotateLeft(eax, 0xb)

edx = eax * 8

edx -= eax

eax = buf5

edx += 0x47c8ac62

eax <<= 8

ecx ^= eax

eax = buf4

eax ^= ecx

eax *= 0x193482ba

eax = RotateRight(eax, 0xf)

eax *= 0x59d87c3f

eax ^= edx

edx = eax

eax = LShR(eax, 0x10)

edx ^= 7

eax ^= edx

eax *= 0x764521f9

edx = eax

edx = LShR(edx, 0xd)

eax ^= edx

eax *= 0x93ac1e76

edx = eax

edx = LShR(edx, 0x10)

eax ^= edx

s.add(eax == 0xf99c821)

s.check()

m = s.model()

print(m)

inp = b""

for b in buffer:

inp += m[b].as_long().to_bytes(1, "big")

print(inp)

Note that for this section I chose to replicate the lower level steps in the disassembly. This is to prevent mistakes from translating the pseudo-C code provided into python for Z3 and allows us to check for mistakes a little more easily when comparing to the original binary.

You can view increasingly lower levels of disassembly in binja by selecting the button in the top left:

Unfortunately, this script gives us something that doesn’t quite match the flag:

[buf5 = 51,

buf3 = 45,

buf2 = 51,

buf6 = 48,

buf4 = 48,

buf0 = 33,

buf1 = 42]

b'!*3-030'

Let’s try to set some characters as not allowed to restrict the set of possible solutions.

from z3 import *

s = Solver()

blacklist = {'`', '|', '-', '?', ';', '{', '}', '[', ']', '\\'}

while True:

buffer = []

for i in range(7):

buffer.append(BitVec(f"buf{i}", 8))

s.add(0x21 <= buffer[i], buffer[i] <= 0x7e)

for c in blacklist:

s.add(buffer[i] != ord(c)) # preventing some characters from being in the solution

# remainder of solve script is same as before

...

Running it again we get our final part of the flag:

[buf5 = 51,

buf3 = 49,

buf2 = 48,

buf6 = 55,

buf4 = 51,

buf0 = 54,

buf1 = 48]

b'6001337'

SEKAI{6001337SEKAIPL@YER}

Challenge Analysis

Since Linux kernel modules and the kernel itself use the ELF specification, reverse engineering one isn’t much different from a regular binary. Running and interfacing with it is surely different, but still not that difficult. In our case the kernel module was still just a compiled C binary and statically reversing it was similar to reversing any other C binary.

On top of that, tools like Z3 and angr are incredibly helpful for these kinds of challenges and can make the process of finding necessary inputs significantly faster.

Overall, this was a great introduction to kernel module reversing and using Z3 for those who haven’t done them before!