Gluttonous Sheep

This sheep needs to chill out with the apples, I’m sure there’s plenty to go around.

Problem Setup

The setup for this problem is quite elaborate, but I’ll summarize briefly as best I can.

The setting for this challenge is a kingdom (aptly named Appleshire) consisting of \(N\) towns, which will be connected by \(N-1\) unique bi-directional roads. We are also told that one can travel between any two towns in this kingdom using these roads.

Hence, we naturally interpret a problem instance as a graph \(G=(V, E)\), where \(V=\{1, \dots, N\}\) is the set of nodes (towns) and \(E \subset V \times V\) is a set of undirected edges such that \(\lvert E \rvert =N-1\). Since we are also told that \(G\) must be connected, \(G\) is a tree.

A town is considered to be abandonded if there is only 1 other town that it is connected to, and otherwise it is considered non-abandonded (i.e. it will have more than 1 neighbor since there are no isolated nodes). Thus, abandonded towns are simply the leaf nodes in \(V\) and non-abandonded towns will be internal nodes.

For a given node \(v\in V\), if \(v\) is a leaf node, we are told that there will be \(L_v \geq 1\) golden apples hidden at that node. Golden apples are only hidden at leaf nodes.

If \(v\) is instead a internal node, then one can instead buy a travel pass from the respective town for the cost of 1 apple. The value of the travel pass available at internal node \(v\) is \(L_v \geq 1\), and one must always have exactly 1 travel pass to travel between towns (if you buy a new one then you discard your previous travel pass). When any given edge in the graph is traversed, you must pay \(L_v\) apples, where \(L_v\) is the value of the travel pass that was last purchased (the edge traversed need not be inident to \(v\)).

Objective

Ok, now that we got all of that setup out of the way, we can discuss what we’re actually trying to accomplish here. Suppose we (by we I mean a sheep named Momo who has purple skin for some reason) start at a node \(u\in V\). From this given node, we are interested in finding a path to a leaf node in \(G\) such that traversing this path maximizes the net number of apples gained (or equivalently, minimizes the net number of apples spent).

This path must end the moment we reach a leaf node. Thus, we must strategically choose what our final destination is. We cannot collect the apples hidden at multiple leaf nodes.

If the minimum number of apples that we can spend if we start at \(u\) is \(c_u\), then we are interested in computing \(c_u\) for all possible starting \(u \in V\).

Note that by the given problem constraints, if our starting \(u\) is already a leaf node, then there is no work to be done, as we will immediately collect \(L_u\) and there is no traversal to be considered. Thus, we really only need to consider \(u \in V\setminus A\), where \(A\) is the set of leaf (abandoned) nodes. I will use the notation \(V\setminus A\) throughout the remainder of this writeup to emphasize this fact.

A Failed Attempt

My first thought for this problem was that the problem creator likely wanted us to leverage the fact that there is a unique path between any two nodes in a tree, and a given problem instance for this challenge is always a tree. Thus, my initial idea involved simply finding this unique path from our starting node to all possible leaf nodes, and determine which is optimal using the observation that during any traversal, if the value of our current travel pass is \(L_{v_1}\), then we should always greedily buy any travel pass that satisfies \(L_{v_2} \leq L_{v_1}\).

This observation comes from the fact that a travel pass only costs 1 apple, and we can only buy them from internal nodes. Since must find a path that ends with a leaf node, we will always end up using any travel pass that is bought, so as long as \(L_{v_2} \leq L_{v_1}\) (note that \(L_v \in\mathbb{N} \;\; \forall v\in V\)) then we will always make up for the 1 apple spent to buy the new travel pass on the very next edge we take.

Unfortunately, it was pretty easy to construct a counterexample for why this would fail. However, I thought it would still be useful to discuss why it fails to get a better grasp of the problem and help motivate the actual solution I came up with.

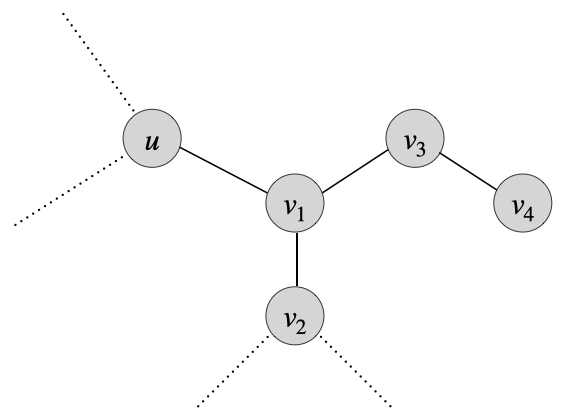

Take the following example, where we are starting at \(u\) and need to end at \(L_{v_4}\) (we can asssume that this is the best leaf node to end at by simply letting \(L_{v_4} \to \infty\)). I’m using dotted lines to simply indicate that \(u\) and \(v_2\) are internal nodes. By this approach, if we simply let \(L_u\to\infty\), \(L_{v_1} \to \infty\), \(L_{v_3} \to \infty\), while \(L_{v_2} = 1\), then it becomes immediately clear that we shouldn’t be taking a direct path to \(v_4\). Instead, it is clearly better to take a detour to get a significantly better travel pass to reduce the number of apples spent along the traversal.

In fact, one can come up with increasingly elaborate example for optimal traversals, where one must make detours during other detours to pick up intermediary travel passes that make it easier to get other intermediary travel passes to then go to the desired leaf node.

Ok, So What Now?

From here, there are two key questions that can be answered to come up with a viable solution.

-

How can we determine when we should take a detour to go get a better travel pass?

-

If we know \(c_{v_1}\) for a given \(v_1 \in V\setminus A\) (recall that \(c_{v_1}\) is the optimal cost if we start at \(v_1\)), can we somehow leverage that result when we need to compute \(c_{v_2}\) for some other \(v_2 \in V\setminus A\)?

Question 1 (Answer: Sort the Nodes)

Let’s tackle question 1 first. Instead of thinking when we should take a detour, we can instead think of when we should not take a detour. The answer to this question is pretty clear: if there is no better travel pass! If

\[L_u = \min_{v\in V\setminus A} L_v\]then there is no better travel pass in the entire graph! Finding \(c_u\) thus simply entails a BFS from \(u\) to all leaf nodes and choosing the traversal that yields the most apples, and at no point do we need to worry about travel passes (since we already have the best one).

Thus, we will ultimately sort all possible \(u\in V\setminus A\) by \(L_u\), and compute \(c_u\) in this order. This is a good segue to the next question, as we will see how doing this leads us to the correct solution.

Question 2 (Answer: Optimal Substructure)

The key observation to answer question 2 is that this problem exhibits optimal substructure (as many graph path finding problems do). Let’s discuss why this is the case.

Lets index the nodes in \(V\setminus A\) as follows,

\[V\setminus A = \{u_1, u_2, \dots, u_{N-\alpha} \}\]such that \(L_{u_1} \leq L_{u_2} \leq \dots \leq L_{u_{N-\alpha}}\) and \(\alpha := \lvert A \rvert\). We’ve already discussed how we can compute \(c_{u_1}\), so let’s suppose we’ve done that already.

Now, suppose we start a BFS traversal starting from \(u_2\), and along the way our BFS reaches \(u_1\). We can observe that once we reach \(u_1\), nothing has changed from when the traversal originated from \(u_1\)! We already know what the optimal path from \(u_1\) is and all decisions to get to \(u_1\) from \(u_2\) are completely independent and don’t change that!

This is precisely optimal substructure. We can more generally state this result as follows. If during the BFS originating at \(u_m\) we encounter node \(u_n\) for \(n < m\), then we can end that branch of the BFS with cost

\[c_{u_n} + c_{u_m \to u_n} + 1\]where \(c_{u_m \to u_n}\) is the cost of getting to \(u_n\) from \(u_m\). Note we drop the \(+1\) term if it so happens that \(L_{u_m} = L_{u_n}\).

And that’s it! Let’s look at what the solution looks like!

Solution

from collections import defaultdict

N = int(input())

# Note that in the arrays below, we keep a dummy placeholder in index 0 to make indexing easier

# vals will store each L_v

vals = [0] + [int(x) for x in input().split()]

degree = [0] * (N+1)

leaf = [True] * (N+1)

adj_list = defaultdict(list)

for _ in range(N-1):

u, v = [int(x) for x in input().split()]

adj_list[u].append(v)

adj_list[v].append(u)

degree[u] += 1

degree[v] += 1

if degree[u] > 1:

leaf[u] = False

if degree[v] > 1:

leaf[v] = False

# Can automatically compute c_u if u is a leaf node - leave all others at 0 for now.

spending = [-x if leaf[i] else 0 for i, x in enumerate(vals)]

# Order nodes by L_u

order = [i[0] for i in sorted(enumerate(vals), key=lambda x: x[1]) if not leaf[i[0]]]

visited = set()

def bfs(root, c):

queue = [(root, 1)]

tmp_visited = set()

tmp_visited.add(root)

best = None

while queue:

node, cost = queue.pop(0)

if leaf[node]:

if best is None or vals[node] - cost > best:

best = vals[node] - cost

continue

for child in adj_list[node]:

if child not in tmp_visited:

if child in visited:

# Add back 1 to account for case of equal travel passes

d = 1 if vals[child] == c else 0

if best is None or -spending[child] - cost - c + d > best:

# Note: the -c term is the cost of getting from current node to next

best = -spending[child] - cost - c + d

else:

queue.append((child, cost + c))

tmp_visited.add(child)

# best tracks apples gained, but we want to store apples spent

spending[root] = -best

visited.add(root)

for node in order:

bfs(node, vals[node])

print(' '.join([str(x) for x in spending[1:]]))

Since we are now also computing each \(c_u\) in ascending order of \(L_u\), we now do not have to worry about making decisions of whether or not we should buy travel passes. From here, the code is a relatively straightforward implementation of exactly the logic discussed in this writeup. I’ve done my best to leave a few comments in the code to explain what I’m doing.

And with that Momo can now optimally hoard his golden apples like the glutton he is!